The Trump administration has taken aggressive action to stall or cancel wind and solar projects in furtherance of a stated objective to “level the playing field” for all types of energy production. The result has been a dramatic swing from the Biden administration, which sought to rapidly expand renewable power sources in the United States, to Trump’s second administration, where the future of solar and wind projects, both planned and in progress, is far less certain.

Through a series of discrete actions, the President and his cabinet have created bureaucratic hurdles to timely completion of routine actions for wind and solar projects—which will result in fewer renewable projects being built and fewer electrons entering the grid. All of this begs the question, how do we continue developing a clean energy economy with a President and his administration that actively seek to slow or obstruct wind and solar development?

On his first day in office in 2025, President Trump signed a litany of presidential actions, including two executive orders and a presidential memorandum targeting wind and solar. Executive Order 14154, “Unleashing American Energy,” took what at first glance appeared to be a technology-neutral stance in advocating for American leadership in energy production; however, if we read the text of the order more closely, there are hints at what is to come. For example, the order establishes a policy that “ensur[es] that an abundant supply of reliable energy is readily accessible in every State and territory of the Nation” (emphasis added). The order goes on to direct an immediate review of agency actions that potentially burden the development of domestic energy sources “with particular attention to oil, natural gas, coal, hydropower, biofuels, critical mineral, and nuclear energy resources,” intentionally excluding wind and solar.

Executive Order 14156, “Declaring a National Energy Emergency,” continued the rhetorical attack on wind and solar by using seemingly innocuous word choices like “intermittent” to refer to wind and solar and “reliable” when referring to other energy sources. The order does invoke emergency authorities to direct agencies to accelerate approval of energy projects—which, when taken in isolation, could include wind and solar. However, the President clarified that wind was not on the table through his Presidential Memorandum signed the same day.

The Presidential Memorandum “Temporary Withdrawal of All Areas on the Outer Continental Shelf from Offshore Wind Leasing and Review of the Federal Government’s Leasing and Permitting Practices for Wind Projects” removed any doubt about whether wind projects were likely to move forward under the “energy emergency.” Although solar still appears to have a lifeline, offshore and onshore wind projects were effectively halted, pending an ongoing review of undetermined duration into the permitting programs that approve wind projects.

In the intervening months since the inauguration, offshore wind projects that were already under construction struggled, with the U.S. Department of the Interior issuing a stop work order for Empire Wind, which was subsequently lifted after a month of negotiating between New York State and the President. Other projects that weren’t yet under construction have continued to be delayed, waiting for final approval or for a notice to proceed. Some projects—like Atlantic Shores South—that had been approved had their permits reconsidered (the Clean Air Act permit in this case) which led to the developer to cancel the current contract with the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities as they wait for more welcoming political winds.

While the offshore wind industry in the United States was effectively paused by the administration’s policies, there was hope that onshore wind and solar could continue, as the deployment of these energy sources is part of an “all-of-the-above” strategy that the President and his cabinet had championed, including during confirmation hearings of Interior Secretary Burgum (see his written responses on the record here) and Energy Secretary Wright (see coverage of his confirmation here). The administration decided instead to slow the progress of wind and solar through subsequent policy actions.

On July 7, the President issued Executive Order 14315, “Ending Market Distorting Subsidies for Unreliable, Foreign-Controlled Energy Sources.” This executive order established that it is the policy of the United States to “rapidly eliminate the market distortions and costs imposed on taxpayers by so-called ‘green’ energy subsidies” by taking an aggressive interpretation of the tax policy changes from the recent reconciliation package, the One Big Beautiful Bill. During the negotiations of that budget reconciliation, negotiators settled on a shorter runway for the renewable tax credits that were established by the Inflation Reduction Act, requiring certain projects to be “in service” by December 2027, or at least to have begun construction by July 4, 2026. The executive order directed the U.S. Department of the Treasury to rewrite the rules around what constitutes “construction,” potentially limiting the number of projects able to leverage the tax credit by making the July 4, 2026, deadline unattainable for many projects through a stricter standard of what is considered “under construction.” On Friday, August 15, the U.S. Department of the Treasury released updated guidance that modified how the Internal Revenue Service considers whether an eligible project is under construction by applying the “physical work test,” which determines whether physical work of a significant nature is underway and is thus sufficient to be considered “under construction” and eligible for the tax credit. This new guidance is a change from the previous threshold that required the project to have obligated at least five percent of project expenditures.

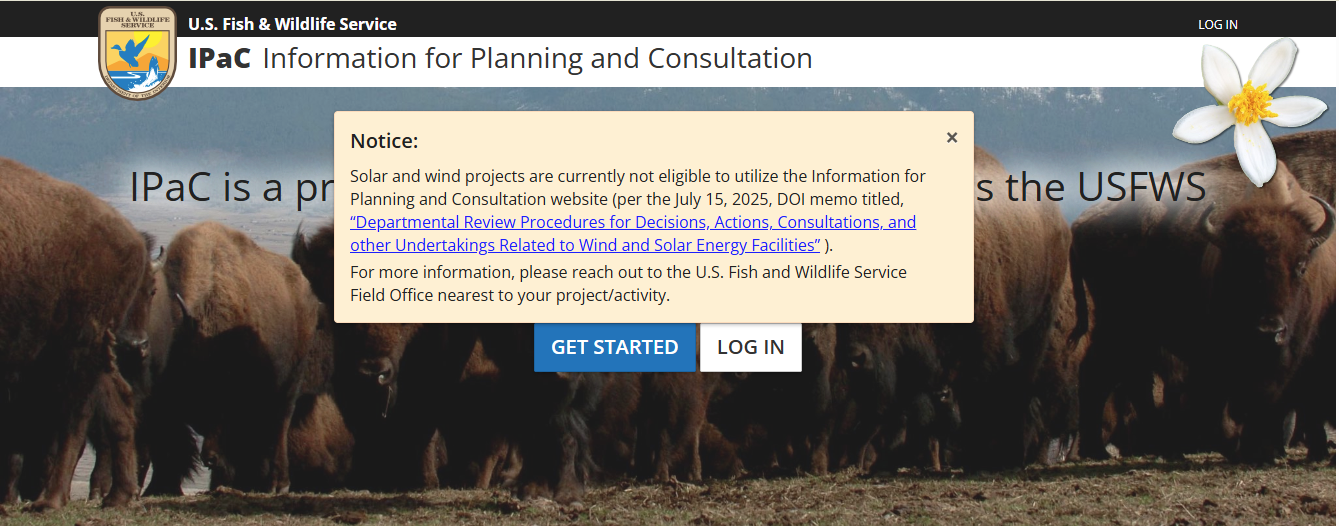

Continuing with the theme of stricter standards, on July 15, the U.S. Department of the Interior issued a policy directive to all assistant secretaries, bureaus, and office heads regarding “Departmental Review Procedures for Decisions, Actions, Consultations, and other Undertakings Related to Wind and Solar Energy Facilities.” This directive requires that “all decisions, actions, consultations and other undertakings … related to wind and solar energy facilities shall require submission to the Office of the Executive Secretariat and Regulatory Affairs, subsequent review by the Office of the Deputy Secretary, and final review by the Office of the Secretary.” Listed within that directive are 68 specific departmental actions, ranging from consultations under the Endangered Species Act and activities related to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to temporary use permits, leasing, site assessments, and more. The effect of this policy requires that ministerial actions that were traditionally delegated down to local offices—for good reason—are now elevated to headquarters in Washington, DC, with no certainty around timing. And most importantly, the policy is not just limited to projects occurring on federal lands: the policy applies to any wind or solar project seeking any U.S. Department of the Interior approval. One of the earliest casualties of this policy was the highly regarded Information for Planning and Consultation, or IPaC, tool, which is run by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to facilitate consultations under the Endangered Species Act.

This online tool, which is used to streamline the consultation process and help project developers navigate threatened and endangered species conflicts, was recently made unavailable for wind and solar projects as a result of the stricter review procedures. This illustrates perfectly the pivot of the administration from a stated all-of-the-above strategy for domestic energy production to a new posture that erects artificial barriers to advancing wind and solar projects.

The administration reinforced this posture with two subsequent Secretarial Orders (SOs), SO 3437, “Ending Preferential Treatment for Unreliable, Foreign Controlled Energy Sources in Department Decision-Making,” and SO 3438, “Managing Federal Energy Resources and Protecting the Environment.” SO 3437, which implements portions of Executive Order 14315 of the same name (summarized above), directed the bureaus within the U.S. Department of the Interior to conduct a review of existing policies, guidance, programs, and other administrative procedures to identify and remedy any “preferential treatment toward wind and solar facilities, in comparison to dispatchable energy sources” (emphasis added). The use of the term “dispatchable” is important here as it refers to baseload energy generation that can be turned on or off—and since we can’t manage the sun or the wind, this would exclude wind and solar projects despite the potential for battery storage to bridge that gap.

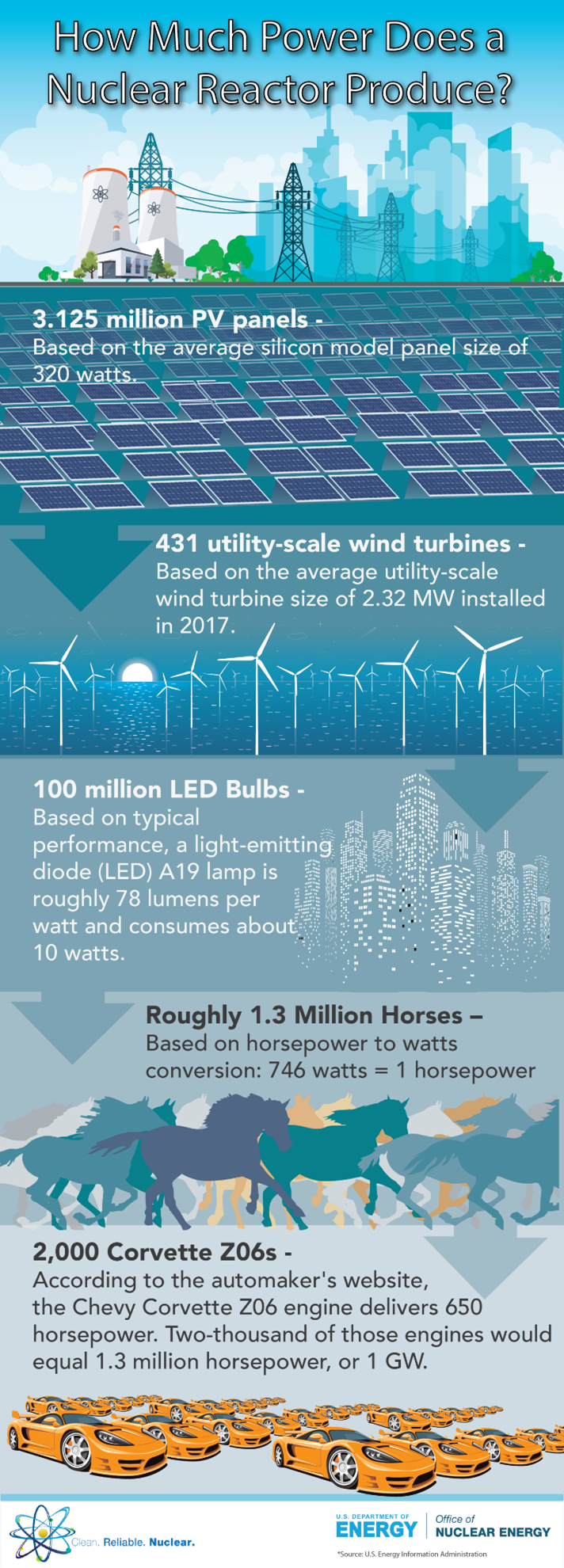

SO 3438 took an even more aggressive step toward blocking the development of wind and solar on federal lands. This SO introduced the concept of capacity density, which at its most basic level refers to the amount of electricity a project can generate divided by its square footage or acreage of land use. The SO argues that because of the lower capacity density of wind and solar, authorizing their development on federal lands is inconsistent with the Federal Land Protection and Management Act’s multiple-use mandate and the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act’s multiple requirements for offshore activities. With that in mind, the SO goes on to direct the bureaus to include in their alternatives analysis under NEPA an alternative energy project with equal or greater capacity density. Further, under this SO, the Department of the Interior “shall only permit those energy projects that are the most appropriate land use when compared to a reasonable range of alternatives.” The guidance is silent on consideration of other environmental effects of the more-dense alternatives such as water usage, emissions, or spent fuel for nuclear reactors, or how that consideration would factor into any final decision.

A plain reading of this policy requires that the U.S. Department of the Interior ignore a renewable energy developer’s proposal to site a solar or wind array and instead consider a more energy-dense alternative—one that is outside the scope of the applicant’s proposal—and potentially select a more capacity-dense alternative, effectively nullifying the developer’s proposal. This clearly contradicts the U.S. Department of the Interior’s own recent NEPA guidance that says that the “purpose and need for a proposed action will also be informed by the goals of the applicant.” It’s reasonable to argue that a solar developer does not have a natural gas plant or nuclear facility as part of their goals, and thus the introduction of such alternatives with greater “density” brings a reasonable comparison of possible outcomes.

Most recently, the President amplified an announcement by Agriculture Secretary Rollins that certain U.S. Department of Agriculture programs would no longer support deploying solar on “prime farmland.” The President’s post called wind and solar “THE SCAM OF THE CENTURY!” and stated that “[w]e will not approve wind or farmer destroying Solar” [sic]. The use of “farmer destroying solar” and the timing of the post would imply a relationship to the Agriculture Secretary’s announcement but that’s far from certain. The President also just initiated a national security investigation into the importation of certain wind turbine components—seeking public input on the risks associated with this energy source. The first casualty of that national security investigation is Revolution Wind, which was already under construction—nearly 80% complete, according to the developer. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management issued a Stop Work Order to Orsted, the developer of Revolution Wind, citing concerns “related to the protection of national security interests of the United States.”

So Now What?

With these artificial obstructions erected to the federal approval of wind and solar projects, the best advice for the moment is to try to site projects where there will be no federal nexus. It is difficult to make that recommendation because I see the value in federal support of these energy projects, but that is where we are today. However, all is not necessarily lost—there is some hope for moving supporting infrastructure forward on federal lands, provided that there is a nexus to the administration’s policy priorities.

The recent Artificial Intelligence Action Plan and subsequent Executive Order 14318, “Accelerating Federal Permitting of Data Center Infrastructure,” acknowledge the need to rapidly build more power generation and distribution infrastructure to support the rapid expansion of data centers. Although the policy recommendations in the Action Plan and the specific direction in the Executive Order maintain their preference for “dispatchable” energy sources, they leave open the possibility that supporting or “covered components” for a data center project may still benefit from acceleration strategies. In this circumstance, a solar with storage project built to support a data center may have the distribution and battery storage elements eligible for acceleration strategies, which could directly or indirectly benefit the primary solar component.

No matter how we come at this problem, the challenge will be how to describe projects in a way that aligns with the administration’s priorities so as to not suffer the administrative burden placed on wind and solar projects. This will take innovation and creative thinking to navigate. But as we’ve just seen with the Stop Work Order for Revolution Wind, even a permit in hand can be paused or rescinded without much warning. This introduces additional uncertainty in the market when a project approval is subject to reconsideration: it makes timelines and predictability unreachable.

Eventually (probably sooner than later) the power that was planned from these wind and solar projects will not come online as expected. Our electricity demand continues to grow, so something is going to have to give. The challenge is what we do in the meantime.

For more insights on federal permitting and ongoing changes, reach out to ESA’s Federal Strategy Director Eric Beightel.