For the more than 100 years—since the creation of the nation’s first highways—America’s roads have connected the nation’s cities and rural communities and linked together our transit, commerce, and transportation system. But this vast network—spanning over 4 million miles—has also greatly impeded wildlife mobility on land and in water. Roads, highways, and travel corridors bisect crucial wildlife migration routes and divide habitat range, placing species at risk.

Across the West Coast, states have been working to help expand and increase species’ access to migration corridors. In Washington, treaty rights and conservation efforts are expanding crucial pathways for salmon migration and fish passage, and in California, new laws and funding opportunities are leading the state’s push to build more wildlife accessibility projects. ESA’s engineers and biologists are supporting these initiatives, assisting on a number of projects throughout these regions.

Salmon in Decline

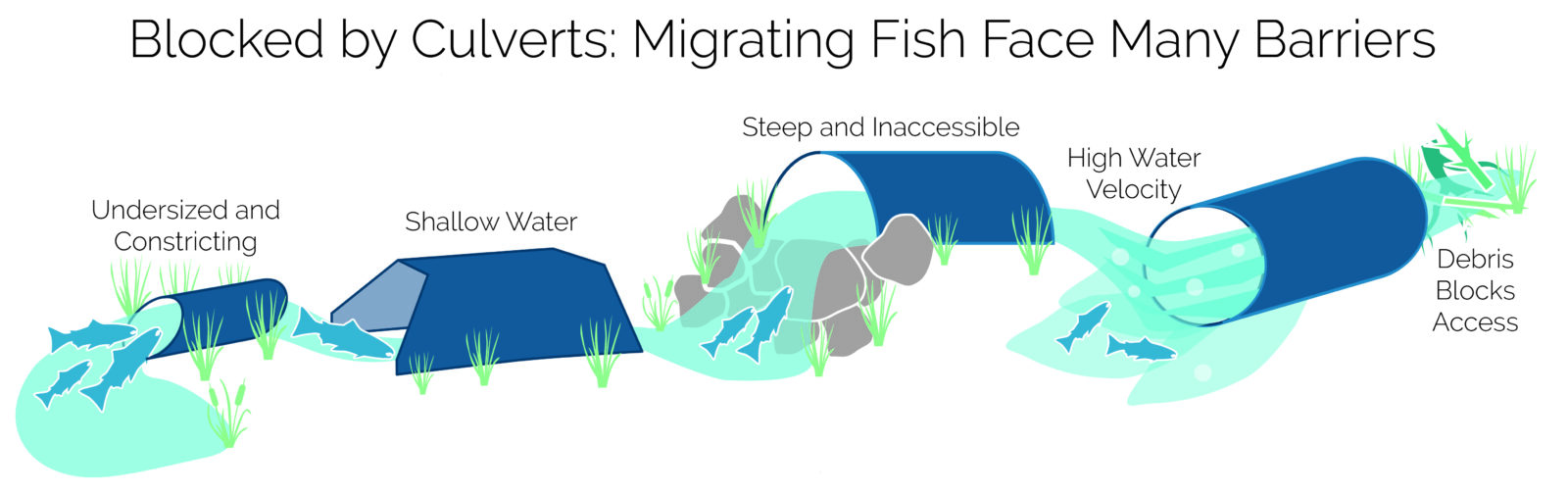

With perpetual snowmelt from nearby mountain ranges, numerous streams and creeks, and characteristic rainfall and drizzle, Washington state is defined by its plentiful water resources. When the state’s roadway network began to form, engineers installed culverts as a means to direct excess water and reduce roadway flooding risk at a relatively low economic cost. Metal pipes and concrete structures were designed to efficiently manage water flows, but they consequently constricted fish migration and blocked fish passage.

It is estimated that out of the nearly 2,000 culverts statewide, more than three-quarters have blocked fish access and habitat. These barriers, as well as dam infrastructure, overfishing, and environmental factors, have contributed to concerning declines in native fish populations throughout the state. The latest State of the Salmon report states that 14 salmon and steelhead population groups in the state are at risk of extinction, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife reports that salmon fishing has declined by more than 80 percent for Coho and 50 percent for Chinook since the 1970s.

These historic declines have notably prompted tribal action. Washington’s landmark 1974 Boldt Decision grants Tribes access to fishing rights and the power to regulate and manage fish resources as co-managers with the State. After witnessing decades of salmon decline, 21 Tribes sued the State in 2001. At the center of this litigation was treaty rights that the Boldt decision afforded—granting Tribes not just the right to fish, but to access healthy fish salmon populations within traditional lands.

In 2013, a state injunction ruling found highway culverts were blocking treaty-based fish access, requiring the Washington Department of Transportation (WSDOT) to correct and replace more than a thousand culverts blocking access to 1,600 miles of salmon habitat by 2030, which was later affirmed in a 2018 U.S. Supreme Court decision.

Not Just Fish Passage

To date, WSDOT has amended over 110 culverts and improved access to 502 miles of salmon and steelhead habitat. ESA is assisting WSDOT, Tribes, and fellow partners with this multibillion-dollar public works program, guiding project design and engineering for numerous efforts in the works, including a project amending six culverts under US Highway 101 near Sequim in the Olympic Peninsula.

The project, which broke ground in 2023, is removing existing barriers along the highway’s stream crossings, replacing them with bridges and other types of redesigned fish-passable structures. The site will also feature new embankments, creek channel grading, erosion control, native planting, and paving.

Leading ESA’s efforts is principal engineer Sky Miller, who has designed more than 85 fish passage projects throughout his 35-year career. While enhancing fish access and restoring native fish populations is the primary goal, an added benefit is that they can also serve a dual purpose in expanding access for other types of wildlife, too.

“This is especially valid,” Miller says, “when project owners opt to construct larger tunnels and widen underpasses at a relatively incidental cost increase. Widening the new span to longer than what the fish passage guidelines require allows mammals to safely cross below the highway, which decreases automobile impacts and increases driver safety.”

One such example is the 236th Avenue NE Safety Improvement Project completed in 2022, where ESA assisted the Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians, leading construction monitoring, habitat restoration, and design of three culvert replacements along a 1.2-mile corridor in Snohomish County. A major component of the project was the modification of the prior narrow 20-inch culvert, which was replaced with a wildlife crossing tunnel spanning 25 feet across, providing ample room for mammals like bear, elk, and deer to safely cross the busy roadway, which lies next to a wetland. So far, wildlife cameras have captured a variety of mammals using the tunnels, including coyotes and deer.

Above, the 236th Avenue NE Safety Improvement Project involved installing three culvert replacements along a 1.2-mile corridor in Snohomish County, including a 25 foot wildlife tunnel.

While the state works to restore the 90 percent of habitat blocked by culverts by the 2030 deadline, ESA will continue to aid clients with design, engineering services, and construction monitoring.

Roads for Miles

In California, natural resource managers are facing a similar challenge along a different kind of network of wildlife barriers—California’s vast highway system.

Stretching across California are 250 state highways, totaling over 15,000 miles. And every year it is estimated that more than 7,000 highway crashes are caused by collisions with large wildlife. Alarmed by these threats to public safety and the severe environmental impact and toll on species, Governor Newsom signed the Safe Roads and Wildlife Project Act into law in late September 2022.

The law requires the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) to identify barriers to wildlife movement and calls on the agency to develop wildlife passage solutions and prioritize crossing structures within proposed roadway projects. In addition, the law also prompts other statewide agencies to adopt new guidelines that promote habitat connectivity projects. These projects can be in the form of building overpasses, underpasses, culverts, and other infrastructure. More than 25 projects are currently under construction or are in planning stages throughout the state, and many more have been completed.

In addition to these statewide regulations, federal funding provided through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is also helping to fund projects and research to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions. Earlier in 2023, $110 million in grants was awarded to 19 projects nationwide, through the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA’s) Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program (WCPP). Amidst the scores of applicants in California, only one was awarded to benefit highway access in the Los Padres National Forest along US Highway 101’s Gaviota Pass.

As ESA’s Southern California Biological Resources Director Terah Donovan shares, the highly competitive process is indicative of a heightened focus on wildlife connectivity. “The demand speaks volumes,” she says.

“We are really seeing that there is a very high need to build wildlife crossing projects across the state. Though the trend is promising, increased funding is needed as the projects advance from planning into construction.”

Terah Donovan, Southern California Biological Resources Director

Forging Connections for Connectivity

Successfully getting a project off the ground requires three components: securing funding, installing wildlife connectivity enhancements, and building conservation through land acquisition.

ESA is currently involved in one such collaborative effort assisting the Santa Clara Valley Habitat Agency’s (SCVHA’s) Pacheco Pass Wildlife Crossing in Santa Clara County. Identified as a California Department of Fish and Wildlife high-priority wildlife crossing location, the project aims to build a crossing across State Route 152, which divides critical mountain lion and deer habitat in the surrounding Diablo and Inner Coastal ranges.

Above, wildlife cameras set up as part of the telemetry study captured mountain lion populations in close vicinity to State Route 152, evidenced by headlights in the background. Photos courtesy the Santa Clara Valey Habitat Agency and the UC Davis Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center.

Overseeing as the project’s manager, ESA helped secure funding—lending writing and application support, which helped SCVHA gain over $7 million in grant funding from the California Wildlife Conservation Board, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and Wildlife Conservation Network.

This funding is now being applied to the planning phase, which includes a feasibility study with an alternatives analysis, an environmental analysis, and a 65 percent design for a wildlife crossing structure. Throughout the past year, ESA has provided directional oversight for technical studies, including evaluating four potential crossing sites, installing directional fencing, and preparing regulatory agency required environmental documentation.

“ESA is committed to enhancing the resilience of species and habitats to climate change impacts.”

Tierra Groff, Wildlife Biologist

“Our work guiding local and regional connectivity projects through all phases of development, from obtaining funding to project design to project construction and monitoring, contributes to increased wildlife connectivity, which allows species to respond to climate change,” says wildlife biologist Tierra Groff, who is serving as the project manager.

Beyond the technical and planning support, a major requirement to successfully implement projects, Donovan explains, is implementing collaborative partnerships. “That means working together with multiagency groups to develop and advance strategies that align with regional, statewide, and national incentives to improve biodiversity outcomes,” she said. “We must also work together to seek funding from private, nonprofit, state, and federal sources.”

Acting as a liaison for SCVHA, ESA has teamed together with the project’s engineering consultants, Caltrans, California High-Speed Rail Authority, technical advisors, and working group to keep the project on track. This spring, the project will begin its 35 percent design phase and teams will be conducting technical studies monitoring elk and mountain lion movement.

It’s all part of the suite of services that ESA provides to help move these projects forward. In addition to serving as a technical partner, ESA can assist clients with grant and fundraising strategies, assessing project budgets, research, project development, and facilitating conservation land acquisition.

For more information about how we can assist on wildlife crossing and connectivity projects throughout the West Coast, please contact Terah Donovan, Sky Miller, and Tierra Groff.