It’s a common sight across the US: a wake of vultures feeding on roadkill on the side of the road. If you’re in certain parts of Arizona, Texas, or Florida, however, you may be lucky enough to catch sight of a rather unique member of the group. Amongst the bald red or black heads pops up a very distinguishable bird with a white neck, orange face, and black-feathered flat-topped head. This outstanding group member is known as the crested caracara.

Many birds, as well as other wildlife groups, are protected at the state or federal level due to various factors that threaten them at a local or national scale. Caracaras are a unique case in that they are afforded federal protection under the Endangered Species Act, but only for the Florida population. The reason is that Florida has what is known as a “relict population,” which is population that, at one time, inhabited a large range but has now become limited to a small area.

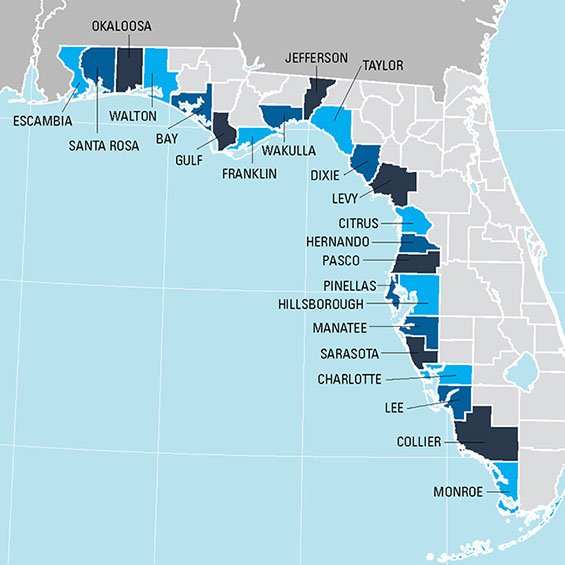

Florida’s relict population is isolated from southern ranges. Source: Wikicommons

Caracaras’ habitat range covers a large area comprising two geographical areas. The southern range encompasses southern Arizona and Texas and extends through Central and South America. However, the northern portion is limited to a small, isolated range in the middle of the Florida peninsula.

Around 12,500 years ago, the vast area between Florida and Texas was covered by an oak savannah. When the latest ice age ended, water from the melting ice filled this area, creating what is now known as the Gulf of Mexico. This separated the range of the species to the western range that encompasses Texas and Arizona to Central America, and to the constricted eastern range that caracara occupy in the small area of Florida.

Unlike their southern cousins, the individuals in Florida’s small range are not migratory. Since the Florida population breeds solely in this limited range, some factors have the potential to be detrimental to the population. For example, if a certain breeding season produces an uneven number of sexes, it has the potential for a negative effect on the productivity of future seasons.

Development in Florida is continually increasing. With more and more people working remotely, the state attracts workers wanting to take advantage of Florida’s climate. With the exception of protected areas, such as state forests and national parks, Florida’s development largely starts on the coasts, due to high demand for beachfront properties, and continues landward. The central portion of the state includes vast pastures. This is ideal habitat for the caracara because, unlike most birds, they need a running start in order to take flight.

Caracara’s ideal habitats are pasture lands dotted with cabbage palms which they use during nesting season. iStock image.

Additionally, many of these pastures include the cabbage palm, a tree that is unprotected otherwise but that is the ideal nesting tree for the species. Since these pastures rarely contain many other constraints, are mostly already cleared, and can easily be purchased from the land owners, they are very attractive to developers.

To help mitigate negative effects of development on caracara populations, ESA staff employs a survey methodology provided by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. If a project occurs within the species’ consultation area, surveys for the species and their nests are required during the nesting season (January 10 – April 30). Sometimes arriving at the office as early as 3:30 a.m., field staff are deployed throughout the consultation area every two weeks.

If a caracara is spotted, the number, developmental stage (determined by the color of the face and legs, which are lighter in juveniles), and direction of flight are recorded. If possible, the bird is followed to see if it lands in a cabbage palm.

A nesting pair of caracaras is spotted through a scope. Photo by BJ Quinton

A high-powered spotting scope is then used to examine the tree from afar. Since the idea behind monitoring the nest is to observe natural behaviors, it is important to stay as conspicuous as possible during these surveys to avoid data inconsistencies or, worse, startling the birds away from their nests. It can be extremely difficult to see into the thick palm fronds, but determined biologists can eventually find an angle to peer into the tree to determine if a nest is present. Once a nest is observed, biologists conduct a productivity survey, observing the development of young caracaras, including the number, effectiveness of adult care, and when they leave the nest.

To ESA’s dedicated wildlife biologists, the early morning hours and long idle stretches of time spent patiently waiting to observe caracaras are just a small part of an incredibly rewarding experience. The excitement of getting to see these unique birds—witnessing their goofy antics as they search the ground for morsels and nesting material, watching the babies grow from helpless fluffballs to fully flighted young in a matter of weeks—makes the waiting and early wake-up calls worthwhile.

ESA biologists have the expertise, and the passion, necessary for tasks like this and are committed to helping our clients maintain the various necessary protection measures to preserve this species. It’s important that ESA staff take time to explain to our clients why monitoring caracara is so consequential, and how we can assist various agencies to successfully meet their project goals and desired results.

According to the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS), bird watching data compiled in 2018 indicated Florida’s caracara population has remained stable, or possibly increased slightly, since the 1970s.

Frank Fichtmueller/Shutterstock

This balance of passions both for the species we admire and for the clients we respect ensures this species will receive the protection it needs in Florida. For more information about how ESA’s wildlife biologists conduct responsible environmental stewardship for caracaras and other biological communities, reach out to BJ Quinton.