According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, more than half of America’s historic wetlands have been lost or disturbed as a result of human intervention. In San Francisco Bay, this number is even higher, at more than 90 percent.

However, starting in the 1960s, changes in how citizens regarded the habitat value and beauty of the Bay, and the resulting policies and actions, led to great strides in promoting restoration projects throughout the region. Those working in the San Francisco Bay region have been actively restoring wetlands for more than 40 years, making it rich in restoration success stories and lessons that can benefit projects throughout the country.

The historic wetland environment of the Bay consisted of more than 540,000 acres of tidal marshes—the largest estuary on the Pacific Coast. The dawn of the Gold Rush in 1849 set the trajectory of rapid population and industrial growth that the San Francisco Bay Area sees to this day. Wetlands at the Bay’s fringe were prime candidates for filling or diking to accommodate agriculture and population growth, as well as for ports for trade and commerce.

Public concern for the Bay’s health began to grow in the 1950s, and reached a tipping point in 1961, when Save San Francisco Bay began its successful movement to halt the destruction caused by filling the Bay. Founded by three East Bay women— Kay Kerr, Sylvia McLaughlin, and Esther Gulick—Save the Bay garnered the support of residents throughout the Bay Area. By 1965, the McAteer-Petris Act—the first wetlands protection in the United States—had passed, preventing further filling of wetlands in San Francisco Bay. This set the course for increased Federal and local interest in the restoration of all areas subject to tidal action, from South San Francisco Bay to San Pablo Bay and all the way up to the Sacramento Delta.

Restoration efforts began in the 1970s, with Dr. H. Thomas Harvey of San Jose State University leading the way. Dr. Harvey taught a prominent pioneer in the field, Dr. Philip Williams—now happily retired from ESA—the significance of the health of the entire wetland ecosystem in relation to the success of a restoration project. And so, 40 years ago, Philip Williams and his team began their career-long pursuit to restore wetlands—starting with the San Francisco Bay.

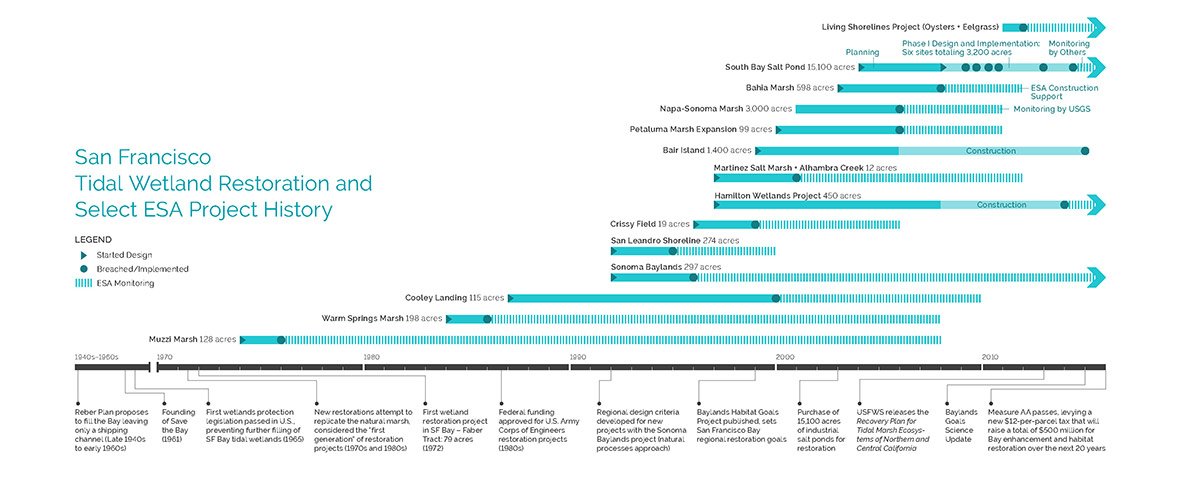

The initial attempts at restoration in the San Francisco Bay were primarily driven by compensatory mitigation requirements. The general approach involved setting the right elevations, planting native marsh grasses and then breaching levees to flood the restored area. These “first generation” marsh restorations were successful in creating a vegetated tidal marsh, however, they typically lacked physical and biological complexity by having only a few, artificially straight tidal channels or low plant diversity. An example of this is Muzzi Marsh, one of the first large-scale restoration projects. Completed in 1976, the 128-acre site was graded and filled to the appropriate elevation of a mature marsh, with the expectation that the “marsh” would immediately start acting like one.

In the 1990s, Williams and the ESA team began to incorporate additional design approaches that rely on the power of natural processes acting over time to create desired wetland features. ESA worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and California State Coastal Conservancy in 1996 to design the restoration of the nearly 300-acre Sonoma Baylands project using this new approach. Imported dredged materials were used to raise the subsided site, but to elevations slightly below a natural marsh, leaving room for tidal flows to form new channels on the land and for bay sediments to build up soils of appropriate quality and texture. Rather than excavate a large channel through sensitive habitat to provide water to the site, tidal flows were used to naturally enlarge a small, existing channel over time. Based on 20 years of data collected by ESA staff, we now know that this approach has been successful.

The 1990s also brought escalating growth in the size of individual restoration efforts, enabling us to apply lessons learned to progressively larger and more complex sites. Our projects jumped from the 300-acre San Leandro Shoreline to the 450-acre Hamilton Wetlands Restoration, to the 1,400-acre Bair Island project, and then the whopping 10,000-acre Napa- Sonoma Marsh Restoration. The largest-scale opportunity for tidal marsh restoration in the Bay came with the purchase in 2003 of the 15,100-acre South Bay Salt Ponds by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and California Department of Fish and Wildlife. This project will not only restore tidal wetlands, but will also provide flood protection and public access for neighboring communities. ESA has been providing engineering and environmental services for the project along 20 miles of shoreline. The first phase of the project restored 3,200 acres of wetlands and 6.7 miles of new trails. Future phases will continue this trajectory and explore the beneficial reuse of dredged material for sea-level rise resilience.

As the projects have evolved, restoration approaches have expanded to address additional issues. Current Bay restoration issues, as documented in the Goals Project Science Update 2015 that ESA staff helped develop, include accelerated sea-level rise, a shortage of estuarine sediments, more extreme weather events, and invasive species. Our projects have also evolved to cover restoration of a broader range of tidal and associated habitats, ranging from oyster and eelgrass areas to upland ecotone slopes that add ecological diversity and climate resiliency. Another consideration for restoration projects is the potential integration of flood protection, which was the case for the Martinez Salt Marsh project. As always, we look to elements of prior projects for lessons we can apply.

The San Francisco Bay Area’s commitment to wetland restoration through these projects and many others has paved the way for similar efforts to be funded and completed throughout the country. In November, the Bay Area region voted to pass Measure AA—a new $12 per-parcel tax that will raise a total of $500 million for Bay enhancement and habitat restoration over the next 20 years. New and existing restoration, flood protection, and public access projects will be eligible for these funds, which can be applied to all project phases, from planning to implementation and monitoring. This is promising news for the health and resiliency of San Francisco Bay. ESA looks forward to being a part of a vibrant future for wetland restoration.

For a comprehensive look at San Francisco’s tidal wetland restoration history with an overlay of select ESA project experience, view our timeline. To learn more about wetland restoration, or to see if your project is eligible for Measure AA funds, contact Michelle Orr.

This story was developed with the help of the following resources:

Callaway, John C., Parker, V. Thomas, Vasey, Michael C., Schile, Lisa M., and Herbert, Ellen R. (2011). Tidal Wetland Restoration in San Francisco Bay: History and Current Issues. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 9(3), 1-12.

Freeman, Robin. (1999). Restoring Healthy Riparian and Wetland Ecosystems: An Interview with Phil Williams. Ecological Restoration, 17(4), 202-209.

Okamoto, Ariel R., and Wong, Kathleen. (2011). Natural History of San Francisco Bay. University of California Press.

Williams, Philip and Faber, Phyllis. (2001). Salt Marsh Restoration Experience in San Francisco Bay, Journal of Coastal Research, 27, 203-211.

San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission

Save the Bay

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge