| Key Takeaways: • It could take a year or more to determine if a waterbody is a WOTUS. • The agencies estimate as little as 19% of wetlands currently mapped by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would be regulated “adjacent wetlands” under the Proposed Rule. • An adjacent wetland must have surface water throughout the entire wet season. • As wetland regulation shifts from the federal government to the states, the regulatory landscape at the state level will become increasingly challenging. |

Like the waters it is meant to protect, the definition of WOTUS has been fluid from 1972 to now, including the effects of the 2023 Sackett vs. EPA Supreme Court decision (Sackett) and the recent Memo to the Field “Proper Implementation of ‘Continuous Surface Connection’”. Despite frequent regulation changes and court cases, WOTUS issues persist. To address these issues, the current administration’s 2025 proposed WOTUS rule (Updated Definition of ‘‘Waters of the United States’’ or Proposed Rule) seeks to:

- Establish a clear, durable, common-sense definition of “waters of the United States.”

- Cut red tape and provide predictability, consistency, clarity, and regulatory certainty.

- Incorporate terms that are easily understood in ordinary parlance and should be implementable by both ordinary citizens and trained professionals.

The Proposed Rule states: “The agencies expect the proposed rule to be deregulatory in nature, and to have cost savings and forgone benefits… Thus, the agencies anticipate that fewer Clean Water Act permits will be required, which will result in cost savings and reduced regulatory burden.” What those cost savings and forgone benefits amount to has yet to be determined by the agencies, as the Proposed Rule’s Regulatory Impact Analysis repeatedly states.

The administration is accepting public comments on the Proposed Rule until Jan 5, 2026. Whether the Proposed Rule succeeds in its goals for simplicity remains to be seen, but it is clear that, but it is clear that, if finalized as proposed, it would reduce the geographic extent of WOTUS nationwide, especially for the arid West.

What Would Change?

The Proposed Rule defines “relatively permanent” to ensure the Sackett decision is fully implemented such that only features with flow (or standing water) sufficient to meet the criteria expressed in Sackett are considered WOTUS. It defines “tributary” to ensure only relatively permanent bodies of water that meet specific requirements are considered jurisdictional.

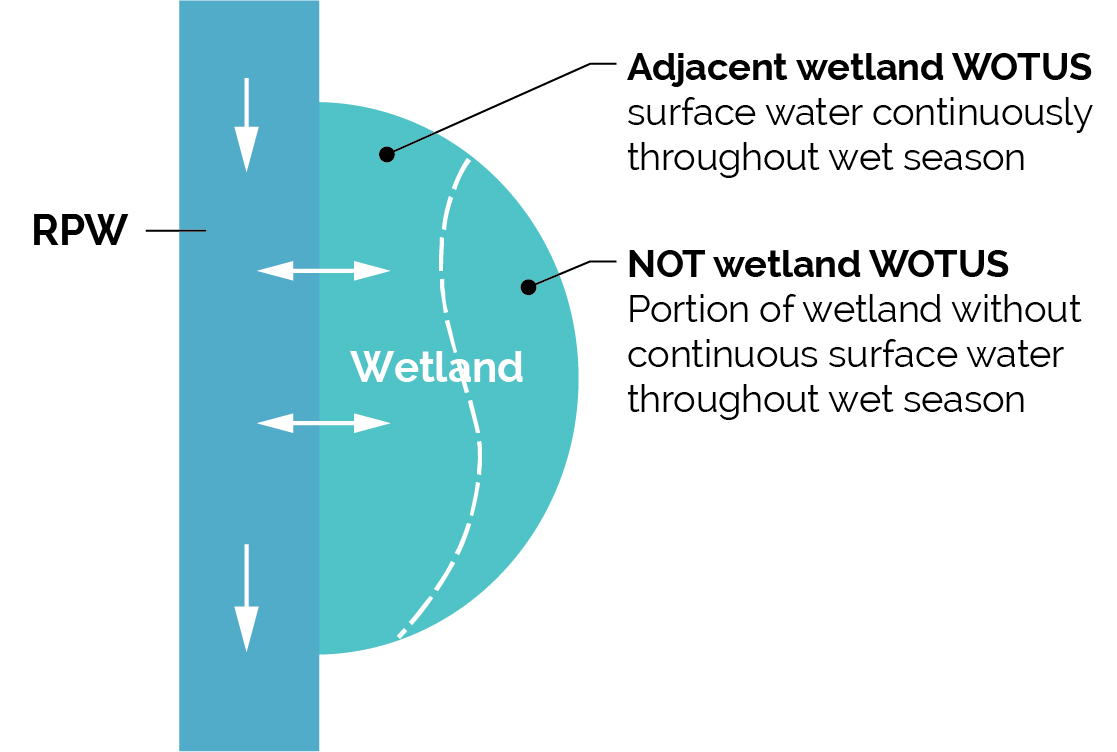

It also defines “continuous surface connection” to fully implement the Sackett decision. This term would require wetlands to meet a new two-part test to be jurisdictional: 1) they must abut a jurisdictional water, and 2) they must have surface water at least during the wet season. And it removes interstate waters from the categories of jurisdictional waters and deletes “intrastate” from the paragraph (a)(5) category for lakes and ponds.

In addition, the agencies are proposing to revise or add the following exclusions:

- Revise the (b)(3) ditch exclusion; and

- Revise the (b)(2) prior converted cropland exclusion,

- Revise the (b)(1) waste treatment system exclusion,

- Add a new (b)(9) groundwater exclusion.

- Underscore that groundwater is not considered WOTUS through a proposed exclusion.

Effects of the Proposed Rule

Under current regulations and case law, ephemeral waters (streams that flow only during and immediately after a rain event) are not considered WOTUS. However, under the Proposed Rule, many intermittent streams that lack surface water throughout the entirety of the wet season would also no longer be considered WOTUS. The Proposed Rule would substantially decrease the extent of regulated wetlands, particularly those not abutting a WOTUS and/or lacking a continuous surface water connection. Going even further, under the Proposed Rule, an adjacent wetland would need to have surface water throughout the entire wet season.

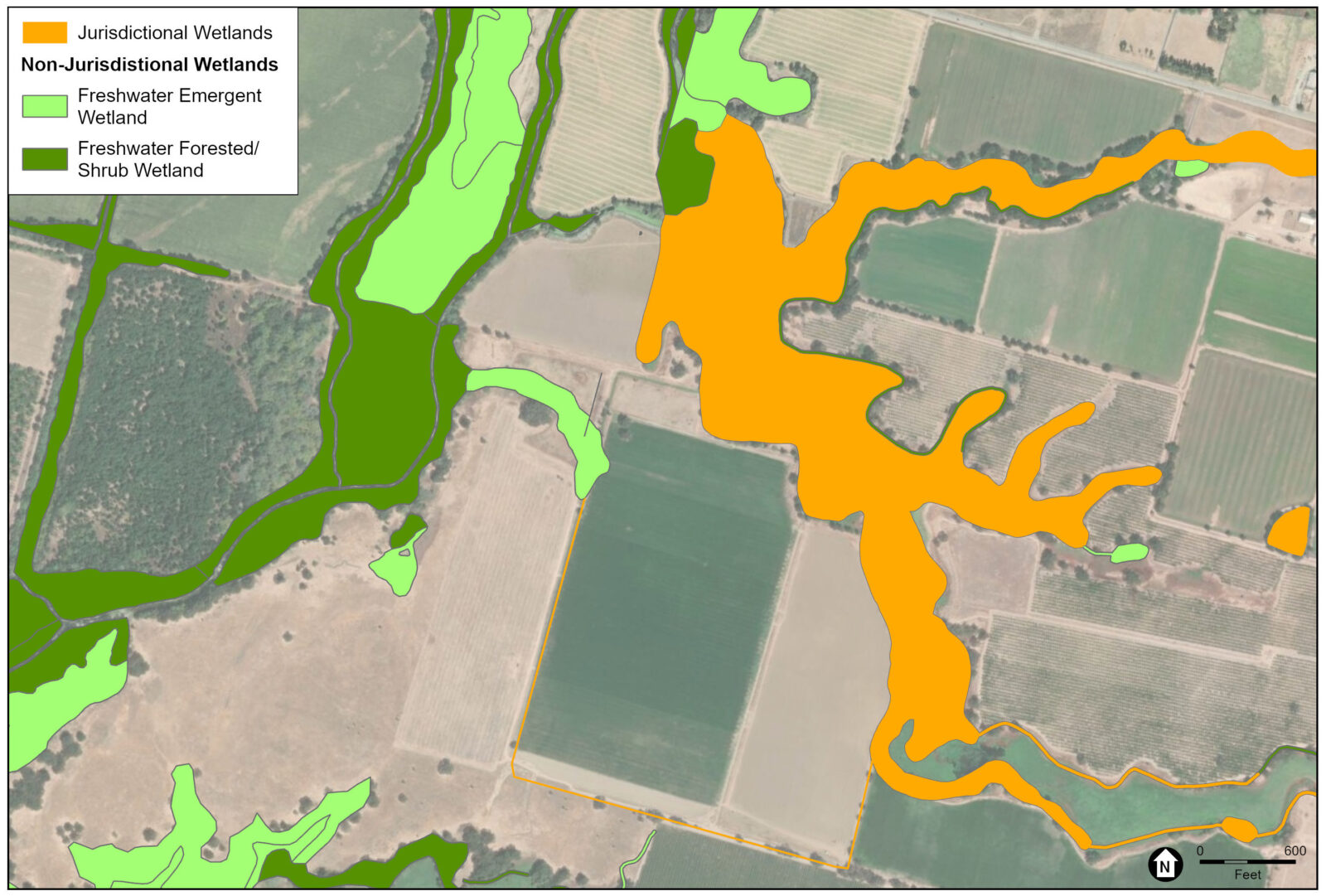

Wetlands without surface water (typically seasonal or groundwater-driven wetlands with only soil saturation) would not have a continuous surface water connection and would not be federally regulated. The agencies estimate that adjacent wetlands under the Proposed Rule would consist of only 19% of wetlands currently mapped by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)[1] representing a substantial decrease[2] in wetland WOTUS.

While the Proposed Rule would reduce the number of Clean Water Act permits issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), it may result in other delays obtaining approved jurisdictional determinations as landowners, project proponents, and agency staff grapple with the Proposed Rule’s jurisdictional criteria.

What These Changes Could Mean For Your Project

These regulatory changes will have broad implications for many projects (click on each below to learn more):

How will the Proposed Rule change a project’s need for a Section 404 permit?

Change in Adjacent Wetlands

- Adjacent wetlands must be indistinguishable from jurisdictional waters through a continuous surface connection, which means that they must abut a jurisdictional WOTUS and contain surface water throughout the entire wet season (except in times of extreme drought).

- Wetlands (or parts of a wetland) without semipermanent surface hydrology, including wetlands with only saturated soil conditions supported by groundwater, would no longer be considered adjacent wetlands.

- Mosaic wetlands under the proposed rule, would not be considered ‘‘one wetland,’’ and would be delineated individually.

Relatively Permanent Water (RPW) Under the Proposed Rule

- Currently, informal practice by some USACE districts is to use previous Rapanos guidance stating a water feature with surface water at least three months out of the year (or less in some cases) has relatively permanent flow.

- Under the Proposed Rule, an RPW would have to contain surface water for the entire wet season.

- However, even the Proposed Rule itself states: “It may be more challenging to identify whether a stream flows year-round or a few days less than year-round. Such methods or the use of remote tools may require repeated or continuous monitoring over the course of a year or longer to ensure water is standing or flowing year-round.” Such monitoring is unlikely to be time-efficient or cost-effective. Even with repeated monitoring, observing let alone delineating thin layers of surface water amid dense vegetation can be daunting whether in the field or viewing remote imagery.

Definition of Tributary Under the New Rule

- Tributaries would be defined as water features that are RPWs, flow downstream to a traditional navigable water (TNW) such as the ocean or certain large lakes and rivers, and would now also have to have a bed and banks. This is unlikely to have a substantial effect on WOTUS determinations as most streams, rivers, ditches and channels exhibit bed and banks.

What if my project has ditches?

The agencies propose defining the term “ditch” to mean “a constructed or excavated channel used to convey water.” Under the Proposed Rule, the updated ditch exclusion would be revised such that RPW ditches would also be excluded. However, consistent with current practice, ditches that are constructed in tributaries or that relocate a tributary would not be excluded.

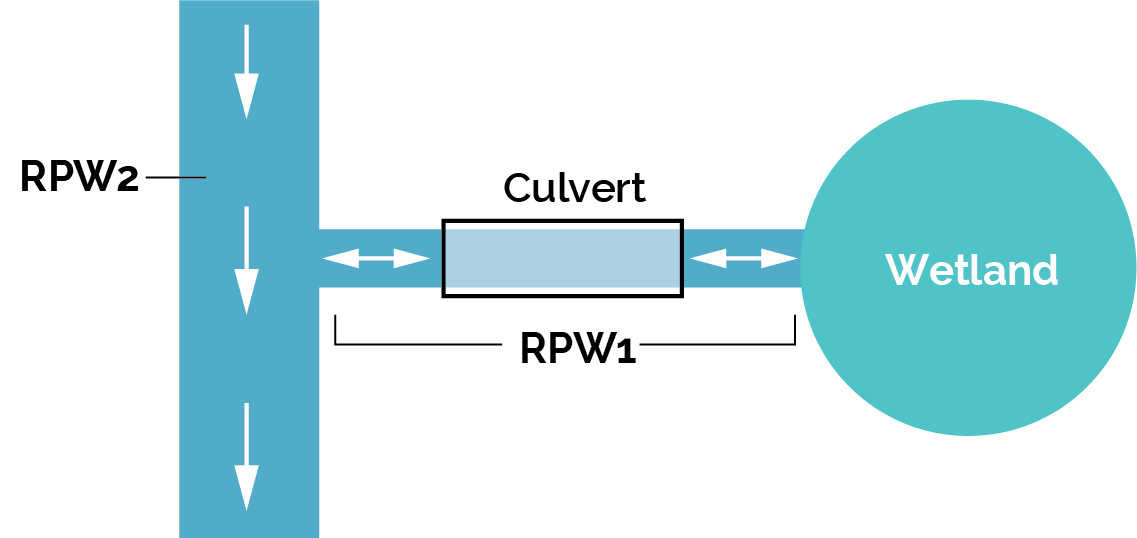

In the case of a tributary that contributes flow to the ocean or a downstream water[1] through an excluded ditch, as long as the ditch has relatively permanent flow, it does not sever jurisdiction upstream under the Proposed Rule. Similar logic applies to wetlands interrupting a tributary.

[1] Paragraph (a)(1) Waters of the United States [currently] means: Waters which are: (i) Currently used, or were used in the past, or may be susceptible to use in interstate or foreign commerce, including all waters which are subject to the ebb and flow of the tide; (ii) The territorial seas; or (iii) Interstate waters, including interstate wetlands;

What about other non-jurisdictional features?

According to the new, Proposed Rule: “Tributaries under the proposed rule may also connect through certain [non-jurisdictional] features, both natural (e.g., debris piles, boulder fields, beaver dams) and artificial (e.g., culverts, ditches, pipes, tunnels, pumps, tide gates, dams), even if such features themselves are non-jurisdictional under the proposed rule, so long as those features convey relatively permanent flow.”

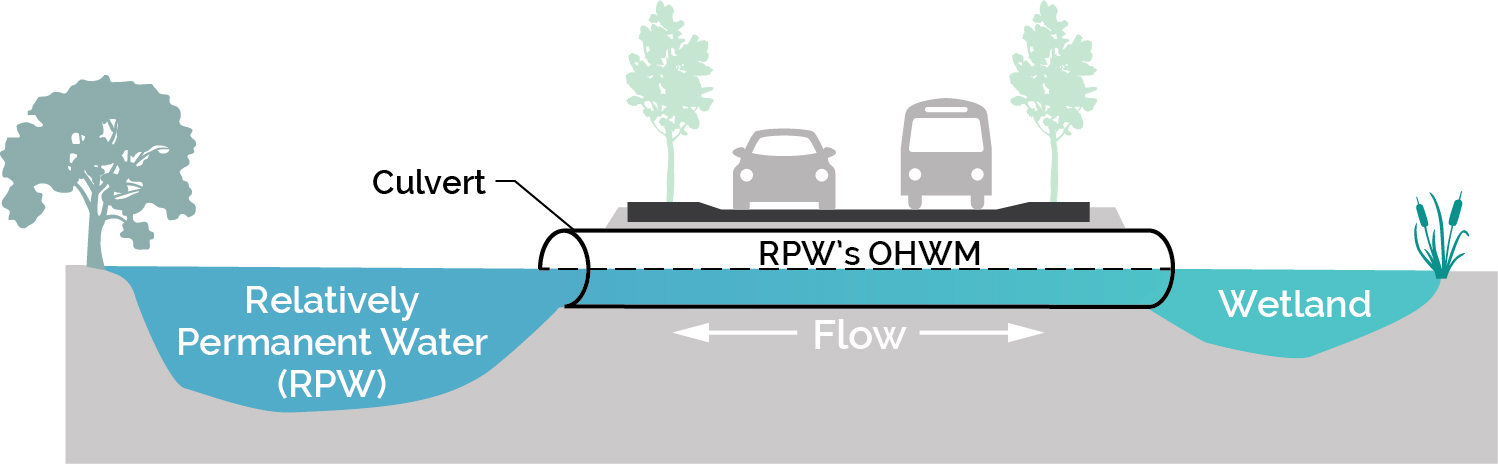

What if my project has culverts connecting wetlands to a downstream WOTUS?

Culverts would not sever jurisdiction when the culvert serves to extend an RPW such that the water directly abuts a wetland, consistent with the March 2025 Continuous Surface Connection Guidance. This would be demonstrated by relatively permanent water flow being present through the culvert as well as an ordinary high-water mark within the culvert.

How is jurisdiction determined?

The new, proposed rule states: “When preparing an approved jurisdictional determination, which is typically made at the request of a landowner or applicant, the agencies bear the burden of proof in demonstrating that an aquatic resource meets the requirements under the proposed rule to be jurisdictional or excluded. However, if the agencies do not have adequate information to demonstrate that a water meets the jurisdictional standards to be a WOTUS, the agencies would find such a water to be non-jurisdictional.“

This represents a substantial change in practice. Currently, if USACE and EPA lack information to complete an approved jurisdictional determination, it is the applicant’s responsibility to provide the required information.

What if I need a federal nexus?

As the extent of WOTUS continues to shrink, it will likely become more difficult to obtain a “federal nexus.” Projects with impacts to threatened or endangered species covered under the Federal Endangered Species Act (FESA) often find it more expeditious to meet their FESA requirements if a federal agency such as USACE consults with USFWS under Section 7 of FESA. However, this only occurs if a USACE permit is needed, creating a federal nexus and triggering a Section 7 consultation. Lacking such a federal nexus, a project proponent is left to consult directly with USFWS under Section 10 of FESA and is required to establish a habitat conservation plan, which can take years to complete before project approval is granted.

State-by-State Approaches

As WOTUS continue to shrink due to Sackett, many states are strengthening their wetland programs, including California, Colorado, Illinois, New Mexico, New York, and Virginia. As regulation of aquatic resources shifts from the federal government to the states, the regulatory landscape within some states is likely to become more complex, rigorous and increasingly challenging for project proponents. Staying abreast of these state changes will become increasingly important.

Most of ESA’s clients are in the following states, but please reach out to us if you have a project in other locations and our experts can consult on how best to navigate statewide wetland programs.

Washington

Waters of the state and wetlands that are non-jurisdictional WOTUS remain protected under state and local laws and regulations. At the state level, impacts to non-federally regulated waters and wetlands must comply with the Washington State Water Pollution Control Act (Chapter 90.48 RCW). Additionally, all shorelines and associated wetlands must comply with the Shoreline Management Act. However, the scope of the SMA is limited and only applies to waters meeting certain criteria. Local county and city codes include critical areas ordinances that provide protection and regulate activities that may impact critical areas including wetlands and other aquatic areas.

To enhance wetland protections, Washington’s Department of Ecology is proposing a new formal permitting program for state waters that are not WOTUS but are regulated under state law (State Waters Alteration Permit). The program aims to create a clear, formal process for permitting impacts to these state waters, which currently lack a formal program and are handled through administrative orders. Final rulemaking may take place sometime in 2026.

California

With one of the stronger wetland protection programs in the nation, the California legislature is attempting to preserve aquatic resource protections in light of the Sackett case, and the Proposed Rule. The Right of Clean Water Act, Senate Bill 609 (SB 601) would amend the state Porter Cologne Water Quality Control Act (Porter Cologne Act) to continue to regulate streams and wetlands that lost federal protection under the CWA due to Sackett. The stated goal of SB 601 is “to restore and retain protections afforded to certain waters of the state prior to May 25, 2023.” If this legislation passes in 2026, it could further complicate environmental regulation in this state and offset deregulatory “gains” made at the federal level.

Oregon

While the Proposed Rule means fewer Oregon landowners will need to obtain CWA permits, the state has its own Removal-Fill law (Chapter 196 — State Waters and Ocean Resources; Wetlands; Removal and Fill), that requires a permit for projects that add, remove, or move more than 50 cubic yards of material in wetlands and waters. Western Oregon has a relatively wet climate compared to many other states and is therefore unlikely to be as affected by RPW-related reductions in WOTUS coverage.

Florida

In the Sunshine State, many ephemeral streams and certain wetlands will likely no longer be under federal jurisdiction. However, the state has a very wet climate, so fewer aquatic resources will be affected by the Proposed Rule. Florida will have a greater role in regulating water bodies that fall outside the new federal definition, which aligns with the goal of strengthening state decision-making. Florida’s goal of pursuing renewed assumption of the 404 Permitting Program may lose its appeal if the Proposed Rule is finalized as federally regulated waters will have been further reduced.

Stay in Touch

Our federal permitting and regulatory experts are at the forefront of tracking environmental developments in this time of rapid change. ESA monitors agency announcements, Federal Register notices, and related litigation, and we’re dedicated to making that information available to you through our on our website.

If you have questions about WOTUS news or want to know more about additional events focused on permitting, please reach out to Dan Swenson, ESA’s Senior Principal Permitting Specialist.

[1] National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

[2] Note NWI data do not account for wetlands already not federally regulated under current regulation