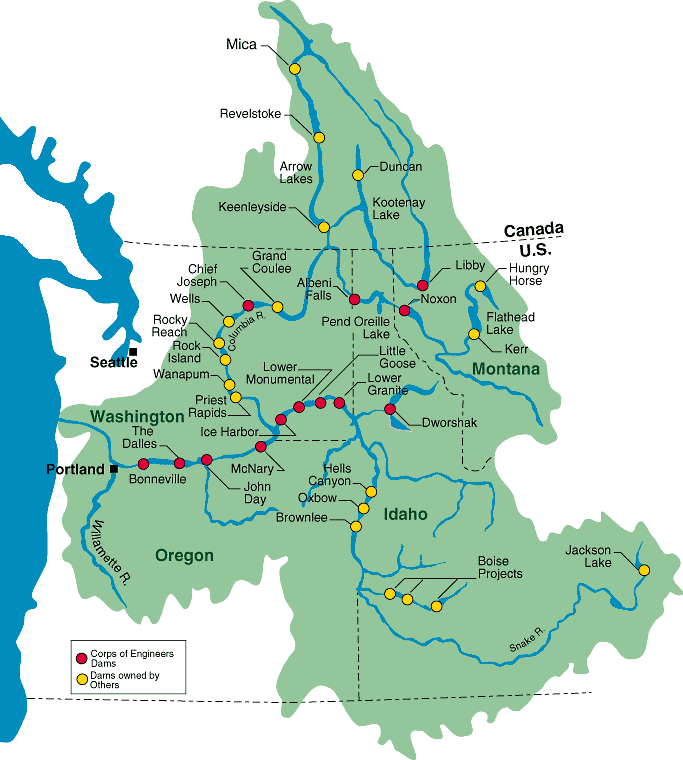

The Columbia River Basin once saw the largest number of salmon and steelhead than any river system in the world. But over the last century, the fish population has declined significantly as dams were built to harness hydropower energy generation for the region. Indigenous tribes have been sounding the alarm since the dams were put in, as fish have long held cultural significance as well as providing their communities with important sustenance.

A map showing the placement of dams along the Columbia River basin. Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

In 1980, these concerns, as well as the federal government’s recognition of the vital importance of restoring fish habitat, prompted change by Congress. The Pacific Northwest Electric Power Planning and Conservation Act (the Northwest Power Act) was enacted to protect, mitigate, and enhance fish and wildlife within the Columbia River Basin.

Authorized by Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, the Act directed that the Bonneville Power Administration—an arm of the U.S. Department of Energy that sells outputs from 29 dams across the Basin—fund these restoration efforts.

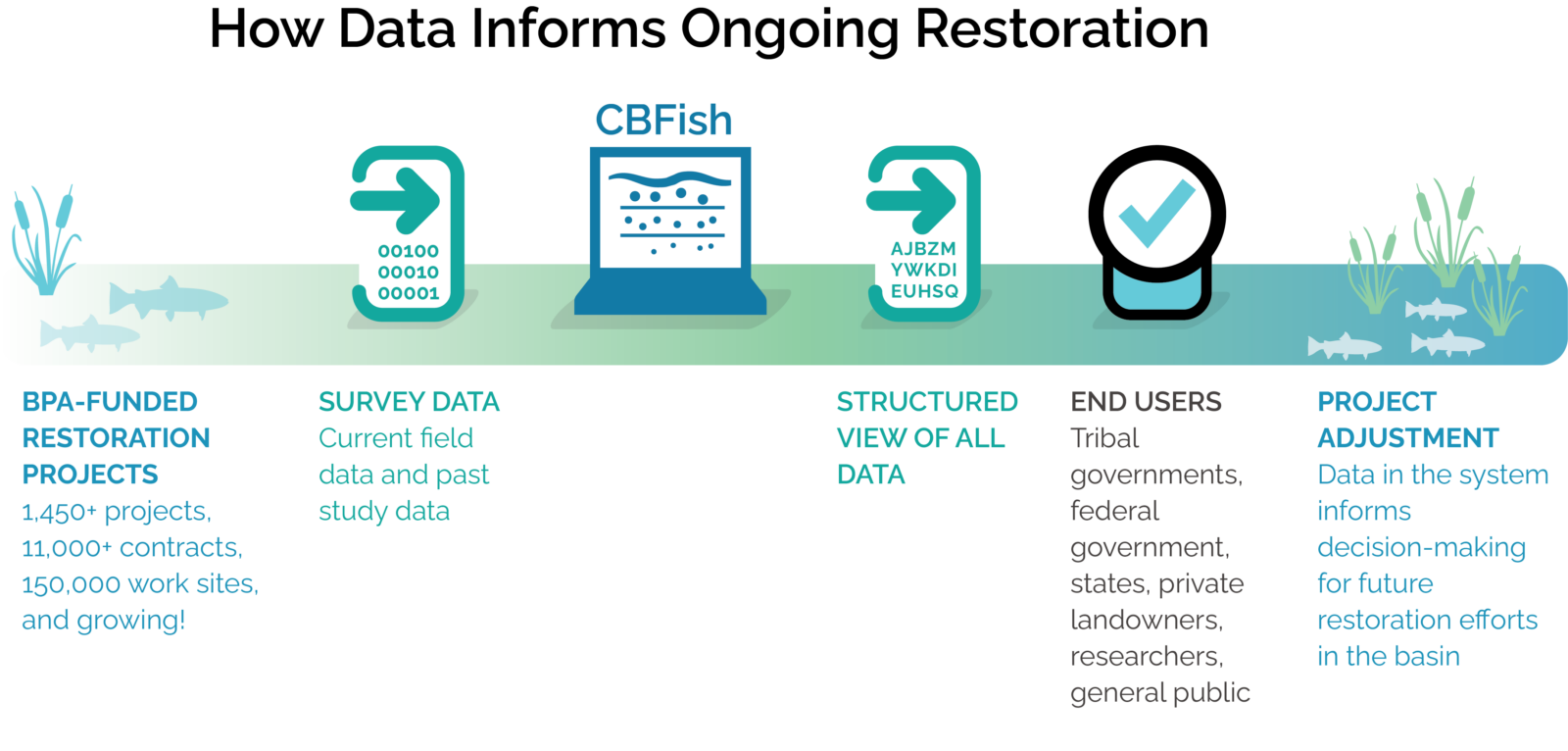

As such, the BPA Fish & Wildlife Program was created, and over the last 40+ years, their portfolio has grown exponentially to a cumulative total of 1,450+ projects, 11,000+ contracts, and 150,000 work sites and counting along the Columbia River Basin. This means there is a whole lot of data that needs to make it to the same place in order to measure effectiveness.

In 2008, BPA realized that the data management system they had was no match for the significant growth in the number of projects. So they brought on Matt Deniston and his team from the newly established environmental data technology company, Sitka Technology Group, which merged with ESA in 2022.

“We take a systems thinking approach to the program…it’s thinking through process improvements and change management.”

Matt Deniston, Data Technology Practice Leader

“Before, it was all paper or stand-alone files—it was all in filing cabinets, Word documents, maybe some spreadsheets in budgets,” says Deniston, who is now ESA’s data technology practice leader. “Now, all of that is highly structured data that can be readily accessed.”

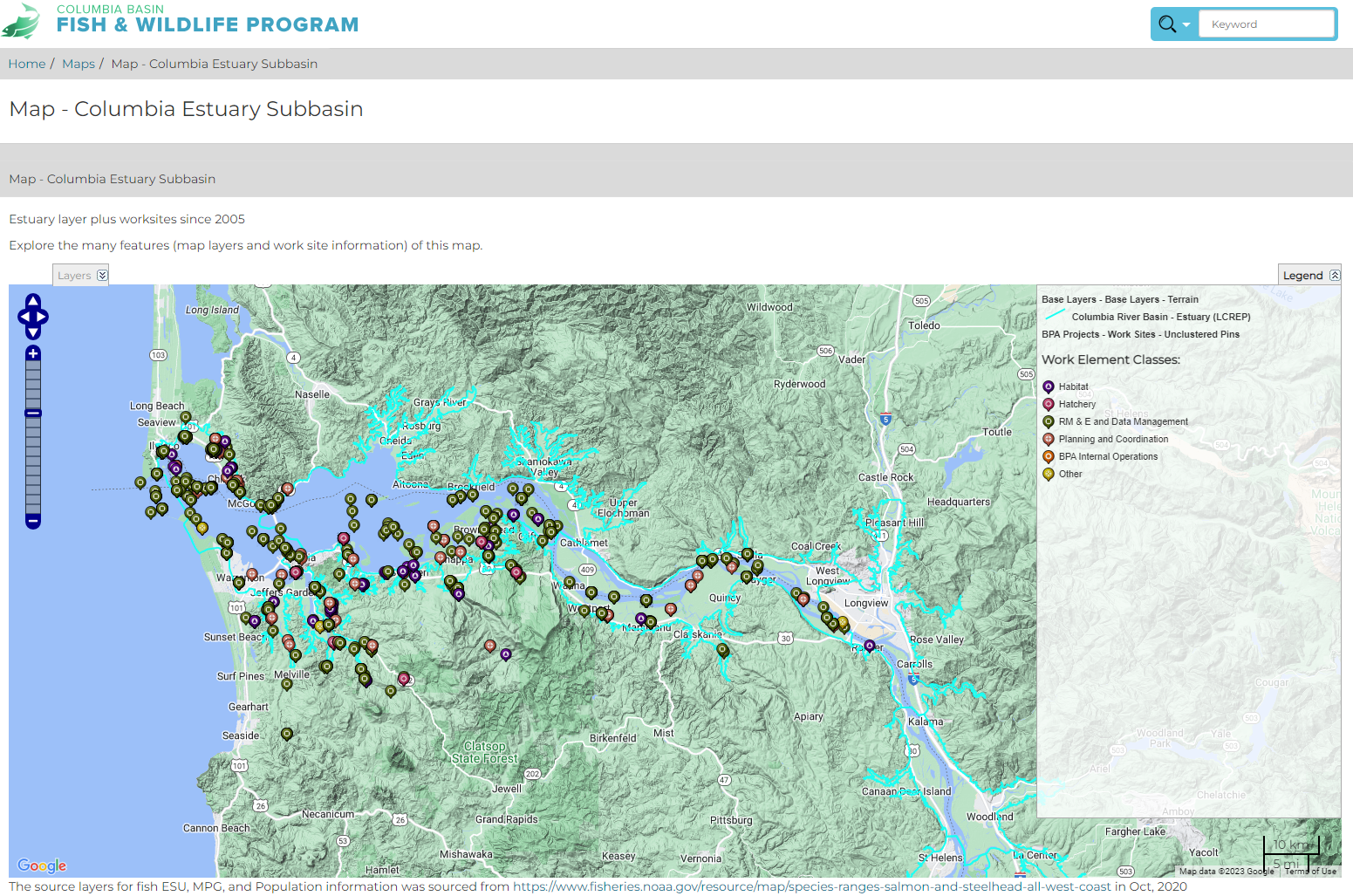

This data structuring process was the result of hard work over the past decade-plus to build CBFish, an interactive data site that gives a comprehensive view of all of the data being gathered through BPA’s Fish & Wildlife Program across the Columbia River Basin.

A screenshot of cbfish’s interactive map, which displays the projects and work sites of the Columbia Basin Fish & Wildlife Program. Source: cbfish.org

“We take a systems thinking approach to the program,” says Deniston. “It’s thinking through process improvements and change management. We might consult on ways to improve a workflow to gain new capabilities, capture new types of information, or enable more informed decision-making.”

The streamlining of data management has made accessing important information much easier for a variety of end users. “There’s an ever-growing amount of publicly accessible information available in cbfish.org,” says Dal Marsters, ESA data technology lead. “Indian tribes, states, the federal government, private landowners, researchers, and the general public can learn about and track the considerable amount of work funded by the Columbia Basin hydropower system each year. Information about everything from salmon eggs to watershed-scale restoration projects.”

This systems approach is important because it reflects the interconnectedness of the entire Columbia River Basin system. There are not only dozens of tributaries that connect with the Columbia River, there are countless streams and creeks that flow from those tributaries that are also essential fish and wildlife habitat.

“A lot of their funding results in restored or conserved habitat in the tributaries and estuary,” says Deniston. These projects come in many forms, including restoring wildlife habitat, improving fish passage, reconnecting floodplains, supplementing fish runs through hatchery programs, and conducting research to inform program direction.

“The ability to call up years of data collected on past habitat restoration projects and combine that with current fish population data to inform a project manager’s planning decisions is so powerful,”

Dal Marsters, Technology Services Lead

While some of the projects seemingly target one specific area, they’re all cumulatively essential for the region. For example, the Colville Tribe is working on the Okanagan Basin Monitoring and Evaluation Program (OBMEP). George Batten, an ESA data scientist, contracts with the Tribe on this program where they’re collecting population data on juvenile and spawning salmon as well as assessing the effectiveness of habitat restoration. They’re also collecting longitudinal data that goes back two decades. “For example, we analyze data which results in maps that identify areas with low-quality habitat, using this information to maximize future investments in restoration,” says Batten.

This data gathering is incredibly valuable for monitoring long-term restoration progress. “The ability to call up years of data collected on past habitat restoration projects and combine that with current fish population data to inform a project manager’s planning decisions is so powerful,” says Marsters.

The ultimate goal is to restore the anadromous fish populations—fish that migrate from fresh water to the ocean and back again—to historic levels. Measuring populations hundreds of miles from the Columbia River itself helps put the data into the context of the entire system.

Since these fish migrate throughout the Columbia River Basin system, data captured at one place and time helps show the impact of the hundreds of projects that CBFish captures that can also help drive future efforts.

“Data are gathered in a variety of ways, such as through screw traps, electrofishing, snorkel surveys, and various tagging technologies,” says Marsters. “These tools help Basin researchers and managers picture where restoration activities are having the desired effect of protecting and strengthening threatened or endangered fish populations.”

Since the founding of BPA’s Fish & Wildlife Program, funding and restoration efforts have grown exponentially to meet the urgency of fish restoration as well as to address the effects of climate change. These efforts to mitigate and restore the Columbia River Basin system are essential to creating a future of sustainable energy that does the least harm to ecosystems therein. And in order to do this, we all need to track progress to identify how each small project is a part of the greater effort to restore and protect the entire system.

To learn more about cbfish.org, visit our website or reach out to Dal Marsters.