For years, it was an incredible story of animal survival in one of the nation’s most urban environments. Los Angeles’s famed P-22, a male mountain lion who earned celebrity status when a National Geographic photographer captured the cat roaming beneath the backdrop of the Hollywood sign, had crossed not only one but two 10-lane freeways, while traversing 50 miles from the Santa Monica Mountains to establish territory in the city’s Griffith Park. The journey was so extraordinary, it was featured in a virtual exhibit at the city’s Museum of Natural History where visitors could try their luck to get across the I-405 freeway and U.S. Route 101.

But in December 2022, the twelve-year-old mountain lion was euthanized, a result of significant injuries suffered in a recent vehicle collision. Just a month later, another cougar, P-81, was fatally struck while crossing the Pacific Coast Highway in Ventura County. Many people find the news of these cats’ vehicular-caused deaths distressing. For wildlife biologists and conservationists, the cougars’ stories are not only devastating but also symbolic of the impacts of the country’s vast roadway network, where one to two million large animals are struck every year by vehicles.

A crucial solution to address these impacts to install wildlife crossings across roads and highways to reconnect animal habitat and reduce the frequency of motor vehicle accidents. Promising new federal and state legislation is helping to fund wildlife crossing projects and enabling transportation agencies to prioritize crossings in infrastructure planning. It will require extensive collaboration between agencies, partnering organizations, scientists, engineers, and environmental consultants to get off the ground.

Critical Habitat Pathways

Across the U.S., 4 million miles of roads and highways have historically divided animals’ natural ranges, creating a patchwork of habitat distribution. This fragmentation limits animals’ mobility to find food, secure mates, and migrate, which not only places them in more peril from having to cross roads but also has the adverse effect of reducing genetic exchange and, consequently, biodiversity.

“Imagine a time when wildlands were wild; we had these animals that moved with the seasons, sought water in rivers, and raised their young,” says Terah Donovan, a senior principal conservation biologist at ESA. “Animals still need to do these things, but their wildlands are much more compressed because we’ve expanded.”

Establishing a safe passage for animals to cross under and over roadways can help reconnect these critical habitat linkages while also allowing them to move in response to factors like climate change.

Wildlife camera footage courtesy Florida Department of Transportation.

Crossings are also one of the most effective means to reduce animal-vehicle collisions and improve public safety. One such example is the Keechelus Lake Wildlife Overcrossing built across Washington’s Interstate 90 in 2018. Post construction, a study found there were one to three fewer vehicle-wildlife collisions per mile spanning a 10-mile radius. Similar studies at other U.S. crossings have found that collisions drop by as much as 80 percent.

Partners in Action

Wildlife crossings come in many shapes and sizes—from culverts, tunnels, bridges, fences, and fish ladders—and they help terrestrial and aquatic species to safely travel across the landscape. Designing effective crossings means integrating local topography and hydrology features and navigating complex land use policies and stakeholder interests within jurisdictions. Transportation agencies, nonprofit organizations, and consultants need to explore these components throughout project development, which often have significant environmental and permitting processes to consider.

“Wildlife crossing structures are transportation infrastructure—and they need to be built with sound engineering, motorist safety, and environmental impacts in mind.”

Terah Donovan, Senior Principal Conservation Biologist

“Processes and procedures set forth by transportation agencies ensure that wildlife crossing transportation investments will meet the same engineering, safety, and environmental standards as all roadway projects. However, this requires additional time, money, and scope to ensure the necessary documents are produced, reviewed, and approved by our collaborating transportation agencies.”

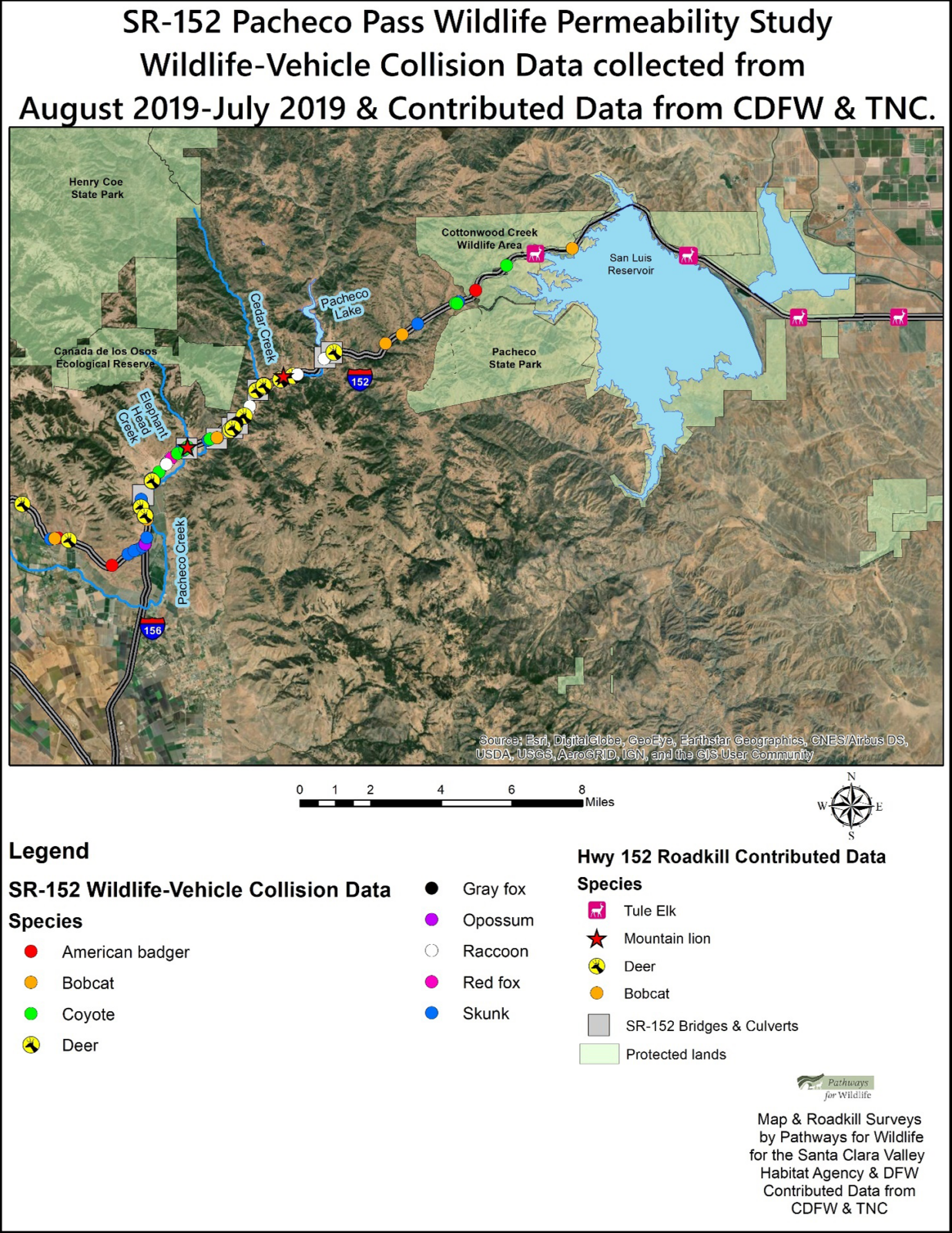

One project underway is the proposed Pacheco Pass Wildlife Crossing across State Route 152 in California’s Santa Clara County. Bisecting open space within the surrounding Diablo and Inner Coastal ranges, this highway is a substantial barrier for the area’s mountain lions, tule elk, badgers, foxes, and other mammal species. Pacheco Pass is also the only area within the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area where these animals have been documented crossing a major highway, making it a high priority for Caltrans and California State Action Plan to enhance connectivity.

The Santa Clara Valley Habitat Agency (SCVHA) conducted a series of wildlife observation studies to assess animal movement, usage of existing culverts, motor-caused animal mortality rates, and species’ habitat use. Now in the project’s planning phase, these ongoing studies are informing crossing feasibility, design recommendations, and alternatives and are largely funded by $5 million in grants awarded by the Wildlife Conservation Board, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Wildlife Conservation Network, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation.

“The Pacheco Creek Watershed is truly a special place; it is a biodiversity hot spot,” says Edmund Sullivan, Executive Officer of the Santa Clara Valley Habitat Agency. “We are excited that this project will increase the permeability of the landscape through scientific rigor, land conservation, and critical crossing infrastructure improvements. Increasing landscape connectivity within and between the Diablo and Inner Coast ranges will allow for measurable improvements for species migration at a landscape scale.”

Donovan, who assisted SCVHA in obtaining grant funding, is serving as project manager. She notes that close collaboration is needed between transportation stakeholders Valley Transportation Agency, Caltrans, and California High-Speed Rail Authority to inform and review planning documents and secure additional funding as the project moves forward into development.

Image courtesy SCVHA and Pathways for Wildlife.

With recent legislation being enacted, such as California’s Safe Roads and Wildlife Protection Act and the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act, transportation agencies are also taking the lead to integrate more wildlife crossings into infrastructure planning.

Working with Nature for Nature

For decades, Florida’s panther population has faced worrisome declines due to vehicle collisions. Every year an estimated 6 to 34 panthers (a subspecies of mountain lion found in south Florida) are struck in vehicle collisions, accounting for an average of 12 percent of their known total populations. Prompted by this alarming trend, the state began installing crossings and bridges modified for panther use.

An interactive “Panther Hotspot” map also charts out sections where panthers are most likely to be hit, and is being used by the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) to better prioritize resources. Image courtesy FDOT.

“FDOT has been a leader in wildlife crossings dating back to the early 1990s, when approximately 40 crossings were constructed along I-75’s Alligator Alley,” says Brent Setchell, Drainage Design Engineer for FDOT.

These crossings are part of a statewide initiative managed by FDOT in coordination with the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), which collaborates with FDOT in the consideration of wildlife connectivity features on any proposed transportation project along or affecting the State Highway System, which are programmed into transportation project costs. So far, FDOT has built a portfolio of approximately 200 crossings, culverts, and modified bridges.

“ESA biologists have worked on the various phases of FDOT projects with crossings for over 25 years, and in that time, the funding and public information available for these projects has greatly improved, leading to the broad support of Florida’s wildlife biologists and the public.”

Sandy Scheda, Southeast Transportation Director.

Designing effective passages for panthers, and other species such as black bears, alligators, bobcats, otters, and amphibians, to use requires close observation of the animal’s travel patterns and a little ingenuity to create a path that animals will follow.

Take for example two crossings installed under Florida State Route 29 a few miles north of the I-75 Alligator Alley in Collier County. Before design began, ESA, in coordination with FDOT, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and USFWS, conducted a series of observational studies to examine local animals’ movement in the heavily forested area.

Determining that panthers and bears were using the area’s natural walkways (breaks in the vegetation and along canals), engineers placed the crossings along these routes. During and after construction, ESA’s wildlife biologists closely monitored these crossings for four years, confirming that these target species were using the crossings, thereby reducing the potential for vehicle-animal collisions and improving motorist safety on this stretch of roadway.

Creating a Place for Animals to Roam

Throughout the US, legislators are taking notice of these successful outcomes, and have passed new laws to enhance wildlife connectivity, such as the federal $350 million Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program funded through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, California’s Wildlife Corridor and Fish Passage restoration grant program, and Florida’s Wildlife Corridor Act. Much publicized projects such as the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing spanning across ten lanes of Los Angeles’s Highway 101, which broke ground in April 2022, are also driving momentum forward.

“This support at the policy and leadership level to advance wildlife crossings is huge,” says Donovan. “It makes these projects more visible and increases funding opportunities.”

Images courtesy FDOT, SCVHA and Pathways for Wildlife.

As these projects break ground, Donovan and Scheda note that crossing structures are just one solution to the broader goal of increasing habitat connectivity across natural and urban spaces.

“It’s also about implementing more policies to complete the fuller picture of reconnecting habitats,” says Scheda. “For example, ensuring that connected habitats remain ‘green’ is also important for selecting crossing locations. Florida’s new legislation incentivizes conservation and sustainable land practices on agricultural lands while allowing ongoing agricultural operations to continue. There are similar federal programs, and both are important to Florida’s goals for connectivity.”

Funding is also a key component to increasing connectivity, as even simple solutions, such as installing fencing, can cost millions. “Constructing new wildlife crossings can be expensive,” says Setchell. “Additional funding to support these structures would help bring them to fruition sooner.”

Supporting Solutions

Integrating wildlife crossings and strategic habitat conservation solutions will require close collaboration with many entities. Having a long history of working with transportation agencies, ESA is well positioned to help navigate the relationships between districts, wildlife agencies, nonprofits, engineers, and the public.

“ESA provides services that align with the full life cycle of wildlife crossing projects,” says Donovan.

Together, ESA can assist our clients with advancing their projects. With a multidisciplinary team of transportation planners and environmental specialists, we write grant applications, conduct geospatial modeling studies and biological monitoring surveys, lead environmental compliance and permitting, incorporate landscape design and habitat restoration, and navigate regulatory processes. For more information, contact Terah Donovan and Sandy Scheda.