Beneath the busy bridge traffic rumbling above, squeezed into a dark crevice no higher than a half-inch tall and shrouded in thick, humid air musty with guano—it’s not exactly what one would think would be a nice place to call home.

But for the tens of thousands of Brazilian (or Mexican) free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) in South Florida, such crevices between expansion and girder joints of roadway bridges serve as an ideal manmade shelter for the bats to roost in during the day, where hundreds at a time can tightly wedge themselves.

With a range that spans throughout the southern United States, Brazilian free-tailed bats play a vital role within Florida ecosystems. These helpful insectivores consume crop-destroying moths and beetles and keep mosquito populations under control and, in turn, the viruses these insects may carry, such as West Nile and Zika. They are also active pollinators and seed distributors, and their guano makes a nutrient-rich fertilizer.

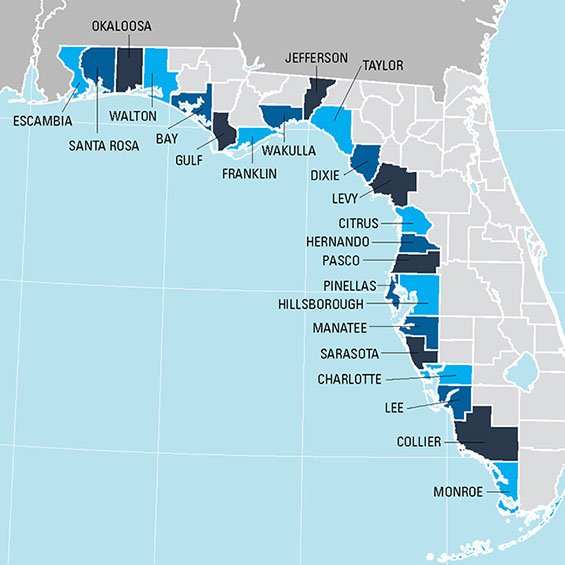

Because of these benefits, Brazilian free-tailed bats and 12 other Florida bat species are protected to conserve bat colony populations through statewide regulations prohibiting human disturbance.

So, when the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) needed to mill, resurface, and replace transverse expansion joints at four of its bridges in Glades County, environmental specialists were needed to assist the agency in safely dislocating the animals to protect them from the harmful vibrations that would occur during construction.

ESA was brought on board for this project, led by Senior Environmental Specialist Tori Kuba, who managed the project’s versatile team, consisting of Southeast Transportation Services Director Sandy Scheda and a team of biologists led by Brendon Quinton.

“Bats are so beneficial, but they have a bad reputation with the public. As with all species, bats are facing challenges related to habitat loss, and they should continue to be protected.”

Tori Kuba, Southeast Transportation Services Director

The first step of the process was an in-depth field study and bridge inspection to locate bat roosting spots, which involved the biologists scanning crevice spaces underneath the bridges with their flashlights. Once all roost and bat sightings were recorded, the team engineered a series of exclusion devices—a network of PVC pipes and wire mesh nets—to place at established openings where the bats were entering.

With these devices, bats can safely exit through the PVC pipes but are unable to reenter because they cannot grip the smooth plastic on the pipes. These exclusion devices act as an efficient and safe solution to direct bats to other roosting sites without causing physical harm, which was a top priority for the project’s design and execution.

During installation, ESA’s biologists made sure to keep their distance from the bats, implementing a “99% hands off” approach, though there were rare times when a few stragglers needed to be handled to move to a safer location using protective gloves. Utmost care was needed for the bats’ delicate anatomy.

or disturb the bats,” said biologist Brendon Quinton.

“The bats are very fragile. To call their wing membranes ‘paper thin’ would be a gross overestimation of their thickness—they are much thinner than a piece of paper. Additionally, the long finger bones are very tiny and could be easily fractured,” says Quinton.

The team was also faced with particular challenges unique to the bats’ not-so-pleasant tendencies—such as having to reconfigure some device installations where bat urine limited adhesion and dodging bat guano. All challenges aside, Tori Kuba sees exclusion methods as fundamental to protecting the species from human activities while steering bats to seek shelter elsewhere such as tree cavities, caverns or bat houses. “These bridges are home to tens of thousands of bats. Exclusions, especially in large roosts like bridges, are important,” says Kuba.

Throughout the bridge resurfacing and construction period, ESA biologists will be on-site monitoring the bats to ensure they are not able to reenter and will adjust devices as needed. Once construction is complete, the devices will be removed and the bats will be able to resettle. Quinton says the project illustrates how a project can apply ESA’s multidisciplinary expertise to solve challenging environmental problems.

“The most meaningful aspect to me was watching how dedicated each member of our team was to not only getting this done efficiently, but also safely, both for us and the bats. Every person that worked on this project showed the same amount of dedication.”

Brendon Quinton, Biologist

Kuba agrees and looks forward to more opportunities to help protect these often-misunderstood creatures.

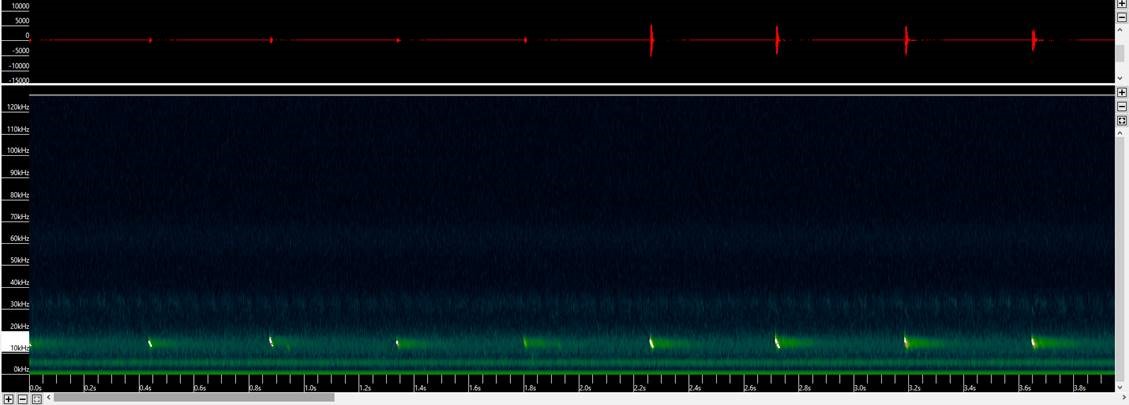

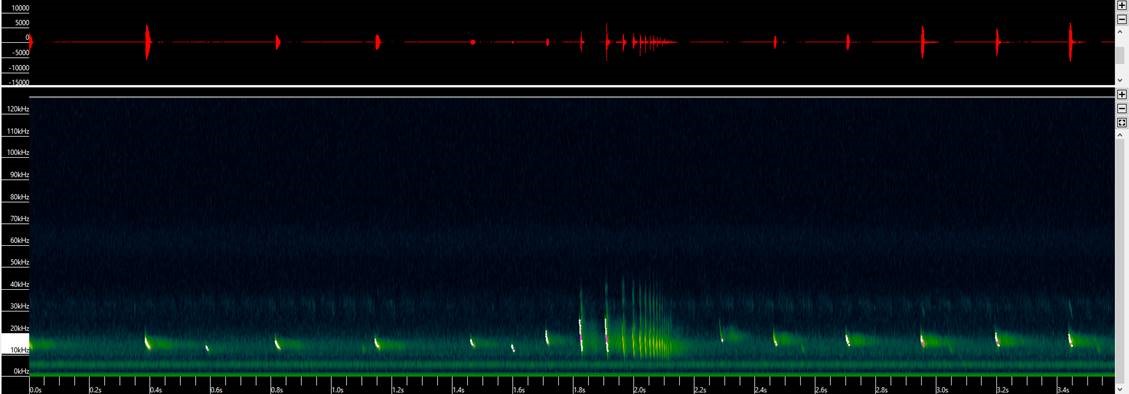

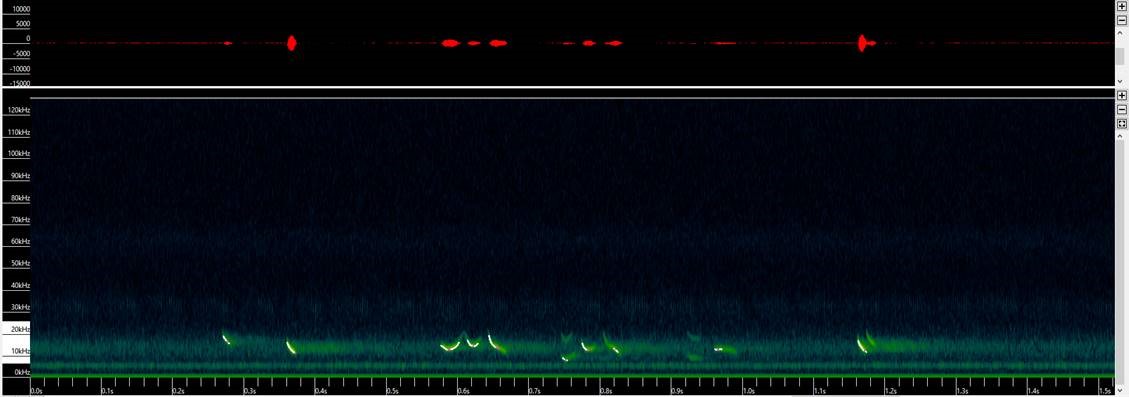

Click the links below to listen to a few of the different calls for Florida bonneted bats. (Note: audio files have been slowed down 8x to allow for human ear detection; real-time calls occur in 1-4 seconds).

Search Phase – Florida bonneted bat pulses to gather information about their surroundings.

Feeding Buzz – After finding their prey, Florida bonneted bats will shoot out pulses with increasing rapidness to hone in on exact location. The increasing pulses show increased locational specificity.

Social Calls – These Florida bonneted bat calls, which deviate from the straight down slope and vary up and down, are essentially a means of communicating with each other.

For more information about ESA’s environmental services for transportation projects—including protected species surveys, relocation, and exclusion strategies—please reach out to Tori Kuba, Brendon Quinton, and Sandy Scheda.