On August 27, 2018, the State of California released its Fourth Climate Change Assessment, which will inform a multifaceted program to defend the state from the effects of climate change. ESA’s coastal engineering team, in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy, Point Blue, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Site Sentinel Cooperative, has developed the Natural Shoreline Infrastructure: Technical Guidance for the California Coast and the related report, TOWARD NATURAL SHORELINE INFRASTRUCTURE TO MANAGE COASTAL CHANGE IN CALIFORNIA; a guideline and toolset for the implementation of natural infrastructure elements as accountable, effective, and sustainable solutions for protecting our shores against sea-level rise.

As part of the same study for the Fourth Climate Change Assessment, we also contributed case study material and support for the first component of the project “Case Studies of Natural Shoreline Infrastructure in Coastal California,” including our work on the Surfers’ Point Managed Shoreline Retreat and Hamilton Wetland Restoration projects.

Along with rising water, sea-level rise will result in higher storm surges, increased risk for flooding, and an increasingly rapid rate of erosion of coastal habitat, and, potentially, damage to valuable public and private development. In years past, engineers may have taken the hard, “grey” design approach of installing a concrete seawall away from shore to break the impact of oncoming waves or hold the line of rising tides. According to a study in 2015, “22,842 km of continental US shoreline—approximately 14% of the total US coastline—has been armored” in this fashion. While this approach may have been the best solution at the time, the tide is changing.

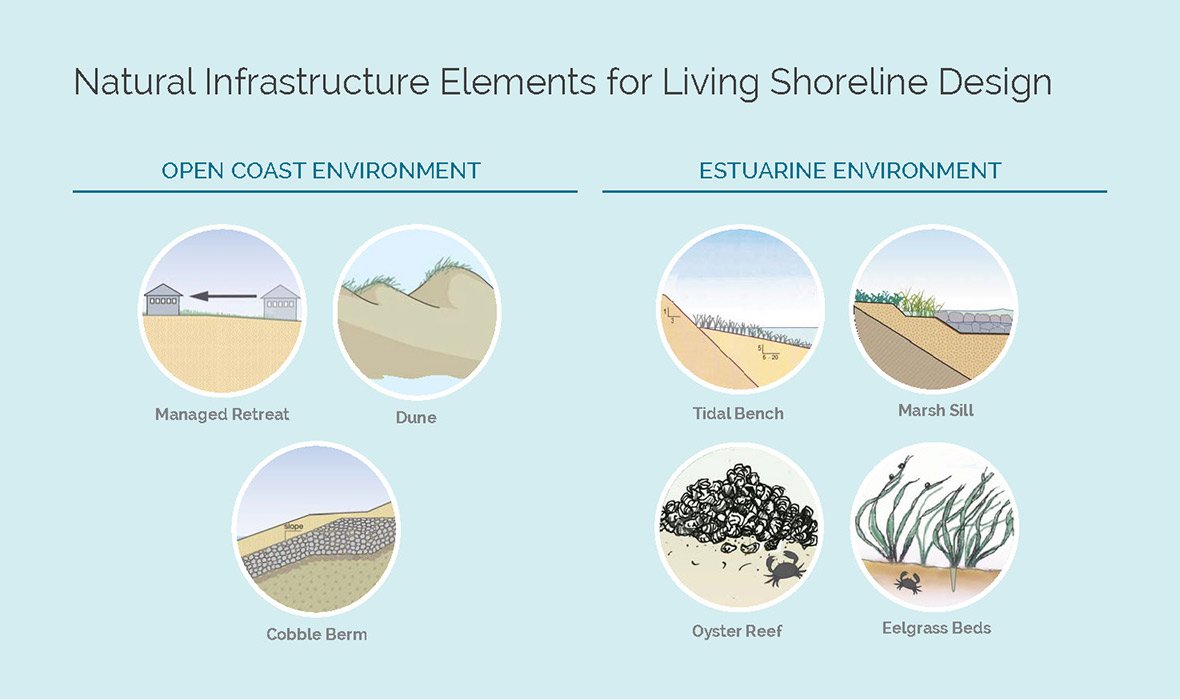

The technical guidance document helps users evaluate the potential for natural infrastructure at a specific site, taking tide range, wave exposure, total water levels, beach width, and foreshore/backshore/planform and possible infrastructure elements into consideration (see examples at right). The purpose of the study is to start closing the gap of technical guidance and boost natural shoreline infrastructure as a replacement for the traditional and more widely accepted armored approach.

Based on our own experience in designing and implementing living shorelines along California’s coast, we collaborated with Point Blue in scientifically and methodically classifying each type of infrastructure with a low-, medium-, and high-applicability rating for the pilot Blueprint web app tool in Monterey and Ventura Counties. These two locations were chosen based on the wealth of project experience the project team has cultivated through decades of work. The geospatial analysis not only indicates the suitability of the natural shoreline infrastructure type at a site, but also shows the additional amount of planform space required to increase a suitability ranking from low to high. This approach applies real-world logic with an understanding that every site is unique and there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Our specialty coastal engineers have a wide breadth of experience spanning across decades and from coast-to-coast. In Ventura, California, we began conceptual planning and design in 1997 for the Surfers’ Point Managed Shoreline Retreat Project. Over time, severe erosion of artificial fill had degraded public access to this popular coastal recreation area, including the collapse of a significant portion of a public bike path and parking lot. ESA provided coastal engineering for approximately 1,800 linear feet of back beach shoreline restoration to more natural conditions, using native materials, grading, and planting, and maintenance of public access recreation opportunities. Part of our approach involved a cobble and sand berm to balance restoration of natural conditions with recreational needs. Today, the team has found that the project has performed as designed, handling erosion concerns during strong El Niño storms. The beach is once again the most visited in Ventura County.

ESA’s scientists have also been working with local municipalities along the Florida coast to combat sea-level rise and flooding since 2000. In one instance, in Tampa Bay’s Safety Harbor, a dilapidated seawall was identified as needing replacement. After speaking with the town about our ability to assist in securing grant funding (be sure to read “Taking Funding for Granted: Resources for Restoration Projects” on page 8) and the long-term benefits of a softer approach, ESA put forward a natural infrastructure design solution. The final design includes removing the existing seawall structure and regrading the bank to match a natural slope, protected by the addition of a triple row of oyster bags. When construction starts in the fall of 2018, the slope will be stabilized with native vegetation. This same approach was successfully employed for the Honi Hanta Girl Scout camp in Bradenton, Florida, where the living shoreline has been functioning as planned for more than a decade and has withstood numerous storms, including Hurricane Irma (Cat 2), which went directly over this site in 2017.

There are times when a hybrid or bio-veneer approach is the only solution, as the seawall cannot be removed because of adjacent infrastructure conflicts. By enhancing an existing seawall with the addition of riprap, specifically designed with soil amendments, these seawall enhancement projects can provide ecological benefits and strengthen the wall’s integrity. While this approach will not mitigate sea-level rise as effectively as a living shoreline, it will provide benefits in the interim. At Ulele Springs in Tampa Bay, ESA removed a section of an existing seawall to re-create an artesian spring-fed creek that existed a century before. The remaining seawall sections were then enhanced with mangrove planters—this was the first “living seawall” done in Florida of its kind. Now, four years later, the mangroves are reaching seven feet tall and holding the rock together, as our designers had hoped.

Living shorelines are being implemented in a number of locations nationally; however, because of regulatory obstacles, these design options are not always considered. To address this issue, in 2015, ESA’s staff co-authored a national report sponsored by Restore America’s Estuaries to assess the regulatory hindrances and identify rule changes that would encourage the implementation of green infrastructure designs. To further encourage the growing acceptance of living shorelines all along coasts, we have been actively engaging with regulatory agencies to streamline the permitting process. On the national side, this has resulted in the recently introduced Nationwide 54 Permit exception, specifically for living shorelines by the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). In many states, after the adaptation of the USACE’s Nationwide 54 Permit, the state regulatory agencies also provided new programmatic exemptions for the permitting of Living Shoreline designs to match the new federal authorization.

Although they are peppering our coasts and bay shores on a national scale, living shorelines are still an emerging science. With the publication of the “Natural Shoreline Infrastructure: Technical Guidance for the California Coast” as part of the Fourth Climate Change Assessment, coastal engineers in California can use it as a blueprint tool to determine the best approach for their site. ESA strives to develop multi-benefit solutions in all of our designs, and we look forward to demonstrating how natural infrastructure can perform against the rising sea levels and manage flood risk while providing ecological benefits as well. To learn more about living shorelines, or to find one near you, reach out to Nick Garrity, Michelle Orr, or Chris Warn.