At first glance, the photographs taken in July 2022 looked like an abstract painting. A craggy mountain shoreline surrounds the blue waters of Lake Mead, the rocky terrain a bold contrast of ivory white and rich brown hues, seemingly divided by an invisible horizontal line. The images, however, were far from abstract. That year, Lake Mead’s water levels plummeted to a historic low level of 1,040 feet—a level not seen since 1937, when the reservoir was first filled—revealing the telltale “bathtub ring,” which consists of distinct lines marking past water levels.

At a Tipping Point

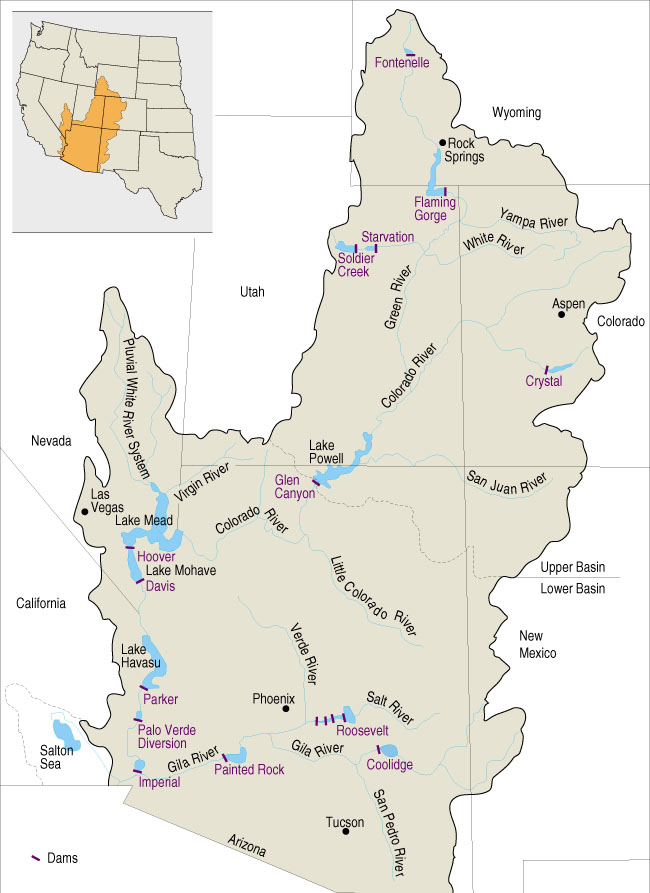

Lake Mead, formed by the Hoover Dam, is the largest reservoir in the US and part of the Colorado River’s massive network of dams, reservoirs, and aqueducts, which supply water to more than 40 million people in seven states and tribal governments. The system is divided into two basins: the Upper Basin, which reaches Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico, and the Lower Basin, which reaches California, Arizona, Nevada, and parts of Mexico.

For over a century, water rights and regulations have divided and apportioned state and Tribal territories’ shares of the river, often through lengthy legal disputes and Supreme Court litigation. In the Lower Basin, California receives the most allotment (also the most basin-wide) at roughly 4.4 million acre-feet, equating to about 27 percent of the Colorado River’s flow.

This volume provides water and hydropower to 13 million households and 600,000 acres of farmland to seven counties in Southern California. Arizona receives the second most at 2.8 million acre-feet, or about 17 percent. Following years of plummeting water levels, water supply in the reservoir has receded to alarmingly low numbers, which the Bureau of Reclamation declared as being at a “tipping point” in 2022.

Years of overallocation, predominantly from agricultural production, which accounts for 74 percent of the river’s diverted water, have drained supply. “There is an inextricable relation to how we manage water in the West,” says Principal Scientist Ramona Swenson.

“What water decisions happen in the Colorado River ripple throughout the Basin with broader ramifications.”

Principal Scientist Ramona Swenson

Climate factors such as drought, evaporation, and reduced snowpack, which are due to rising temperatures, have also caused levels to sink—studies report that as much as one-third of Lake Mead’s water has been lost from evaporation.

A Plan for Water Conservation

Prompted by the alarming trend, the Bureau of Reclamation initiated the Lower Colorado Conservation Program, calling on the seven states to develop conservation agreements and lower their water use, with the goal to conserve at least 3 million-acre feet of water through the end of 2026 through voluntary water cuts and improving system efficiency.

Following the program’s enactment, the federal government announced it was investing $4 billion through the Inflation Reduction Act toward the Colorado River and other western projects to address drought resiliency, including $700 million that the Department of the Interior announced just this June. The funding will augment management efforts by irrigation districts, cities, and Tribes to curb water use, and will fund resiliency-focused projects involving conservation, conveyance, water recycling, infrastructure and pipelines, groundwater storage, and water quality treatment.

Since the immense strategic effort began, water districts have been taking proactive steps to reduce water demands and have made noticeable progress in pulling back their use in just a few short years. In 2023, Arizona, California, and Nevada reduced water consumption by 13 percent, the lowest annual reduction in 40 years.

In Southern California, water districts have implemented new management strategies and policies, such as drip irrigation, agricultural fallowing (paying farmers dividends to refrain from growing crops), water transfers from other municipalities, and enacting community water restrictions, to meet conservation goals outlined in the LC Program. These management actions are making positive headway to address the water crisis, but also present challenges to farmers and ecosystems that rely on that water, notes Senior Water Principal Tom Barnes.

Biological Impacts

Winding across 1,400 miles from the Rockies to the Pacific, the Colorado River and its tributaries cut through tall mountain canyons, arid landscapes, and deserts, serving as a lifeforce for species across the Southwest.

There are 26 native fish species that are found only in the warm-water canyons of the Basin, including the Colorado pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus Lucius), humpback chub (Gila cypha), bonytail (Gila elegans), and razorback sucker (Xyrauchen texanus). As the Colorado River’s network of dams has cut off prime habitat access over the past century, these species are largely dependent on controlled streamflows. But with the added pressures of water diversion mandates taking effect, dam operations, and prevalent invasive species, two-thirds of native fish are now considered to be at risk—as their populations are on the brink.

Endangered wildlife that rely on riparian vegetation at the river’s edge, such as the southwestern willow flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus), are also threatened. Water cutbacks mean less water flows to downstream riparian habitats, floodplains, interlocked lakes, and upland habitats, which require specific hydrological conditions to sustain and are already stressed from increased temperatures and drought.

“We need to think about the end-use impact,” says Barnes. “How we manage water use will directly affect the downstream ecology both in the river channel and in off-channel areas that rely on water diversions.”

Aware of these concerns, the Bureau of Reclamation is monitoring how reduced water flows, implemented through System Conservation Implementation Agreements (SCIAs) in coordination with water districts, affect both ecological resources and water users.

ESA is providing ongoing support to the Bureau during the three-year conservation program. Water management and biological resources specialists have been closely studying the potential effects of water reduction on federally listed species within aquatic, riparian, and upland environments within the river’s lower main-stem. These specialists have produced an Environmental Assessment based on their observations and data.

ESA has also been supporting Southern California water districts participating in SCIAs by developing mitigation strategies, supplementing Habitat Conservation Plans and NEPA and CEQA documentation, securing permits, and conducting compliance monitoring.

As Barnes notes, balancing the dual needs of conserving water and minimizing risks to natural resources is complex and requires close coordination with water users and wildlife regulatory agencies. Water agencies and managers need to honor water rights allocations and participate in conservation while also considering the ecological impacts and the financial effects on agricultural producers and urban water users.

“As conservation reduces water availability in the arid Southwest, opportunities will arise to increase our awareness, and to focus our efforts on adaptive management of vulnerable ecosystems and sensitive species supported with reduced supplies, which will require a multi-regional collaboration effort,” says Barnes.

An Integrated Approach

One thing for certain is that managing water resources in the Colorado River and impacted watersheds downstream will require complex decisions to protect vulnerable species and ecosystems, as well as the well-being of millions of water users, in the face of water scarcity and climate issues.

Solving these kinds of unique challenges requires a dynamic team of environmental specialists who are ready to take these challenges head on.

“ESA has intrinsic understanding of this line between water supply, water management, and biological services. And we understand the close coordination and solutions required to address the integrated nature of these resources.”

Tom Barnes, Senior Water Resources Principal

For more information about ESA’s integrated experience in water management and conservation and how we can help you, contact Tom Barnes and Ramona Swenson.

This is the first of two articles exploring how ESA is helping to study and manage environmental impacts along the Colorado River and its tributaries. Stay tuned for our next article focused on our work in the Salton Sea.