All eyes are on Tampa Bay.

In early April, emergency crews began draining millions of gallons of high-nutrient wastewater from the Piney Point diked storage reservoir in Manatee County, Florida. National news covered the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s decision to save the homes and lives of nearby communities—including the evacuation of hundreds of residents—as a tear in a plastic liner at the bottom of the reservoir raised concerns about its potential for complete collapse.

The liner’s job was to contain the “process water” that remained after the bankruptcy and abandonment of a fertilizer plant led to an ill-advised attempt to use the fertilizer plant’s wastewater reservoir as a dredge material disposal site. Not only did the liner failure create structural integrity issues, it also raised concerns about the nutrients and contaminants present in the water itself. Once the water was pumped into Tampa Bay, scientists and stakeholders began anxiously debating what the effects may be on this critical habitat.

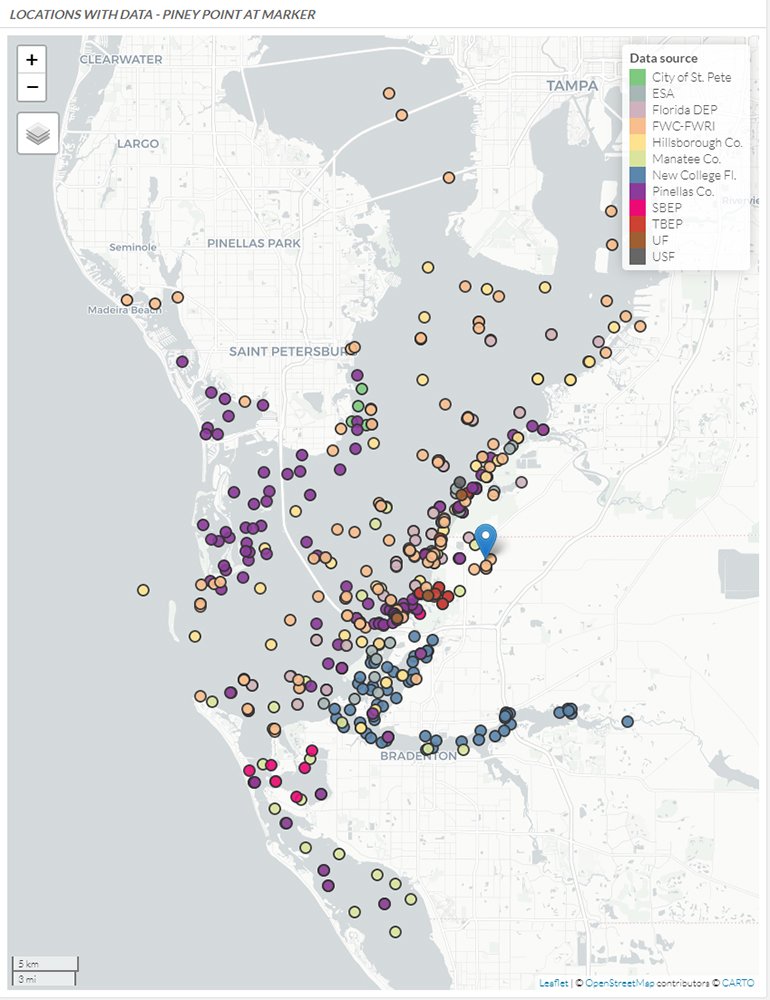

Tampa Bay has one of the best and most data-rich, long-term monitoring programs of any estuary in the U.S. The Environmental Protection Commission of Hillsborough County has been monitoring water quality, invertebrates, and plankton in the Bay since 1975. Manatee County, Pinellas County, the City of St. Petersburg, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission’s Fish and Wildlife Research Institute also conduct extensive monitoring in the Bay.

The Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP) and neighboring Sarasota Bay Estuary Program (SBEP) had just begun exploring adding a regional macroalgae monitoring program because of a potential data gap in information needed to successfully manage the estuaries. Macroalgae are a large, plantlike marine species, similar in size and sometimes shape to seagrasses, and are natural components of healthy Florida estuaries. However, excessive microalgae growth, or “blooms,” can have negative ecosystem consequences. In recent years, scientists have become concerned that intense macroalgae blooms in Florida estuaries could damage seagrass habitats and affect water quality.

Within days of the initial spill, ESA scientists were out in the most remote areas of the Tampa Bay, collecting essential baseline data before discharges affected the ecosystem.

Over the last 30 years, ESA’s water quality and restoration scientists have been working in and around Tampa Bay’s 2,200-mile watershed. We have monitored seagrass growth, examined the impacts of increased nutrient loadings on its habitat, and monitored freshwater inflows. In addition, we prepared the Tampa Bay Blue Carbon study in 2016, and completed the TBEP Habitat Master Plan in 2020. When Piney Point’s water began flowing into Tampa Bay, other organizations like the SBEP, the Counties, and the University of Florida Center for Coastal Solutions quickly volunteered to assist the TBEP in implementing a macroalgae monitoring program. As a trusted consultant and stakeholder, ESA also volunteered to assist in the program—the only private sector entity to do so. Within days of the initial spill, ESA scientists were out in the most remote areas of the Tampa Bay, collecting essential baseline data before discharges affected the ecosystem.

TBEP is hosting the Piney Point Environmental Monitoring Dashboard, where all monitoring data are hosted and shared to keep a finger on the pulse of how the area’s water quality, benthic species, seagrass, and fisheries are responding to the discharge. (Source: TBEP)

ESA then monitored 16 sites in the shallow back bay areas of southern Tampa Bay over the three months following the spill to document any ongoing effects. Teams recorded the condition, weight, and area covered by both submerged seagrasses and macroalgae in shallow and often isolated areas of the Bay that were not being monitored by the extensive water quality monitoring programs initiated in response to Piney Point discharge. Water quality monitoring programs observed little or no increase in nutrients following the discharge, but the macroalgae monitoring documented the onset of the worst nuisance algae blooms seen in Tampa Bay for decades. The areas affected by macroalgae blooms correspond with the areas that hydrologic models predicted would be impacted by Piney Point discharges. During the final weeks of monitoring, ESA staff observed a significant decrease in macroalgae abundance at the same time a harmful “red tide” algae bloom was beginning in Tampa Bay.

The State of Florida is keeping the community up to date with a Red Tide Current Status site, which is updated daily by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Here you can find maps like the one above that shows the red tide (Karenia brevis) events in your area. (Source: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

Some experts are hypothesizing that the nutrients were not observed in the water column because they were quickly absorbed by macroalgae growth. Once the macroalgae died, the nutrients were released into the water column and immediately taken up by the red tide algae organism Karenia brevis. Eastern Tampa Bay is now undergoing a serious red tide harmful algae bloom that has killed millions of fish. It is thought that the Piney Point discharges may not have caused the red tide bloom, but that it likely made it far worse than it would have been otherwise. The macroalgae monitoring data are still being analyzed, but they will ultimately be the information that either provides evidence of the nutrient pathway from the spill to the red tide event or suggests a different cause for the red tide. This determination will be a key factor in making appropriate legal, regulatory, and resource management decisions to best protect the current and future health of the Bay.

TBEP is hosting the Piney Point Environmental Monitoring Dashboard, where all monitoring data are hosted and shared to keep a finger on the pulse of how the area’s water quality, benthic species, seagrass, and fisheries are responding to the discharge. ESA is committed supporting TBEP in their mission to protect this significant body of water and critical habitat area. If you are moved to do the same, please join us by getting involved with TBEP’s “Ten Ways to Save the Bay.” When we all do one thing, we can make a difference. For more information about our boots-on-the-ground work in and around the bay, reach out to Robert Woithe.