According to the Department of Water Resources’ Water Year 2023 report, the State of California experienced “weather whiplash,” with the water year starting off in drought conditions and ending with 141 percent of statewide average precipitation and 137 percent of April 1st snowpack. The state’s above-ground reservoirs, which are averaging 90 percent full, are all above historic average levels as of spring 2024 and don’t have additional capacity. How can a drought-prone state capture and store more of this precipitation for future use?

Let’s look deeper at the topic of water storage—as in underground—and explore two approaches that California water managers are taking to not only manage floodwaters but also recharge groundwater aquifers, which are important and unseen components in water supply management.

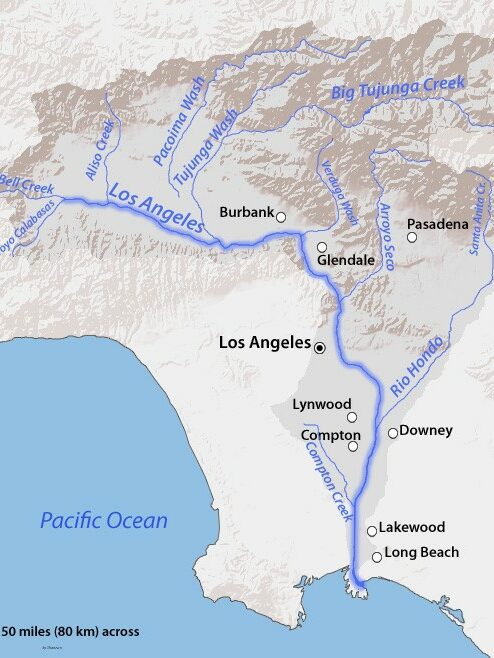

Los Angeles County’s Stormwater History

Before Los Angeles became California’s most populous county with 9.6 million residents, the San Gabriel Valley was a dangerous place to live during the rainy season. With the San Gabriel Mountains directing stormwater into the valley below like a giant funnel, the area regularly suffered from flooding during large winter storms. There were particularly devastating floods in 1934 and again in 1938 that resulted in fatalities and destruction and prompted the county to action. The solution was the installation of concrete channels that created a deliberate and safe route for stormwater from the mountains out to the ocean: the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers.

These channelized rivers have been critical in keeping the region safe from flooding, but get a deserved side-eye when the semi-arid, drought-stricken region is looking to store more fresh water. Combined with the area’s population density and abundance of paved surfaces, this has pushed LA County to be creative in capturing and storing stormwater.

Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permits

A key driver in managing stormwater runoff—and a major contributor to underground stormwater capture—is actually the result of water quality regulations found in the federal Clean Water Act. The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit program, a part of the Clean Water Act, requires urbanized areas with populations of more than 100,000 people to obtain and implement Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) permits. These MS4 permits originally established stormwater management practices to minimize pollutant runoff, but have also promoted infrastructure that retains stormwater on site, resulting in increased deep percolation.

Specifically, the MS4 permits require LA County to capture the first ¾-inch of runoff from every storm to avoid altering natural waterways and to control pollutants like sediment, fertilizers, pathogens, and toxic chemicals. This has posed a challenge for LA County, but has also led to various innovative solutions.

Innovative Stormwater Capture and Results

According to a recent LA Times article, the region has invested over 1 billion dollars since 2001. LA County has stored roughly 295,000 acre-feet (nearly 100 billion gallons) of water since last October, enough to supply 2.4 million residents for a year, through their reservoir improvements and groundwater recharge efforts. ESA has been part of this success by supporting the County’s Department of Public Works in their goal of having more reliable and local water storage in the County. ESA prepared the Programmatic Environmental Impact Report that evaluated the effects of building and managing the infrastructure required by the MS4 permit throughout the County. ESA has subsequently supported numerous municipalities as well as the County in evaluating specific projects tiering from the Programmatic Environmental Impact Report.

Cities in the region have implemented various stormwater capture projects funded through local means, ranging from underground storage caverns beneath parking lots to in-situ treatment systems that encourage water infiltration into the area’s permeable alluvial soils. ESA has recently provided environmental compliance services for the City of Los Angeles Department of Water and Power’s stormwater capture program. In addition, new spreading grounds have been set aside for increased recharge potential. These projects not only meet federal regulations, they also replenish the groundwater, allowing for safe drinking water extraction.

“I want Angelinos to know that local municipalities are doing good work to capture this water” says Sarah Spano, Southern California Water Group Director.

“It’s important to share that these systems are functioning to divert a large quantity of stormwater back into the ground for future use.”

Sarah Spano, Southern California Water Group Director

Looking to the North: The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and the surrounding Central Valley are also at the mercy of stormwater coursing off the largest mountain range in California: the Sierra Nevada. Runoff from this 400-mile stretch of mountains serves as the primary source of flow into the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, especially during the spring, when snowmelt from the mountains swells their volume.

The Delta is where the rivers find common ground on the valley floor: a vast, complex estuary that is not only critical habitat for numerous species, but that also plays a crucial role in the water resources of the state. The land is broad and near sea level, making it prone to large-scale flooding, especially during intense storm events.

Flood management has been a priority in the Delta, and balancing infrastructure needs (such as levees), the safety of the nearby communities, and habitat conservation has required a multidisciplinary, multi-benefit approach.

Flood-Managed Aquifer Recharge in the San Joaquin Valley

According to the 2023 US Census and this report from California 100, the San Joaquin Valley has a population of roughly 4.3 million residents across eight counties (Fresno, Kern, Kings, Madera, Merced, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, and Tulare). For reference, that’s less than half of LA County’s headcount in an area that spans 8.4 million acres. Since 60 percent of the land in these counties is farmland, this is an ideal region for Flood-Managed Aquifer Recharge (Flood-MAR) — a sustainable and innovative water management technique that addresses water scarcity and flood risk.

“Flood-MAR involves capturing floodwaters and using them to recharge underground aquifers,” explains Jim O’Toole, Director of Practices at ESA and ESA’s Water Market Lead.

“Essentially, when rivers or streams overflow during heavy rainfall, excess flows are allowed to access the floodplain in designated areas, which can provide multiple benefits: flood management, food web activation for salmonids, and groundwater infiltration.”

Jim O’Toole, Director of Practices

Runoff from the mountains is directed to designated areas, which can be natural like wetlands and floodplains, or constructed like ponds and infiltration basins. This water then infiltrates down into the soil and replenishes the underlying aquifer. By harnessing the power of natural processes, this offers a sustainable and environmentally friendly approach to water security.

ESA has been supporting Flood-MAR by developing a set of environmental indicators and associated quantitative metrics that allow for evaluation of the effects of Flood-MAR on sensitive aquatic species across the five major San Joaquin River tributaries. In addition, our team has helped inform potential reservoir reoperations under Flood-MAR to provide environmental flows critical for specific salmonid life stages, and has developed a groundwater accounting platform that allows water managers and the public to monitor groundwater levels and helps the state to achieve sustainability.

A Multi-Benefit Solution

Flood-MAR is a multi-benefit solution offering increased water security, flood mitigation, groundwater quality, climate change adaptation, and ecosystem restoration. While the successful application of Flood-MAR will require suitable land and upfront investments for planning and maintenance, the positive impact on groundwater aquifer recharge can mean a great deal to an area like the San Joaquin Valley that experiences periods of extreme drought but that also has the potential for flooding during intense storm events.

No “One-Size” Solution

Whether looking at a highly urban and developed region like LA County or the more rural San Joaquin Valley, ESA has been supporting our clients in pursuing innovative aquifer recharge processes that achieve results. Understanding an area’s individual geology, hydrology, biology, and land-use culture plays a critical role in determining the best approach.

As a state that routinely faces severe drought conditions, capturing the water when it is falling is critical and cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. If you would like to learn more about innovative ways we are assisting our clients in storing stormwater, reach out to our groundwater submarket leader Tom Barnes.

Top image: Aerial view looking south west at a section of the San Joaquin River and Hog Island, part of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta in San Joaquin County, California. Photo by California Department of Water Resources