More than 73 miles of the Puget Sound shoreline has railroad tracks that are either on or near the shoreline. Built between 1870 and 1910 to connect to a nationwide rail network to transport goods and people, much of the rail line was initially constructed on trestles, a series of cross-braced wood frames with open spaces in between, along the shoreline to elevate the railroad above the water. More recently, the trestles were backfilled and hardened with ballast and riprap to form a solid embankment or causeway for the railroad line to reduce maintenance costs. Culverts or occasionally bridges were installed through the railroad embankment to allow streams to drain into Puget Sound.

An unintended consequence of these embankments and the culverts is that they interrupt the natural connection between the watershed and Puget Sound and disrupt natural processes, such as the delivery of water, sediment, wood, and organic matter into the nearshore. Another significant impact of the existing culvert crossings is that they partially or fully block fish passage routes used by anadromous salmon and trout migrating between coastal streams and Puget Sound.

Along the 73-mile route, existing embankments, culverts, and other railroad crossing structures limit fish connectivity between native streams and Puget Sound.

This restricts access for several species of anadromous salmon and trout who use these habitats for spawning and rearing, as well as young Chinook salmon that join from other river systems and are are listed as threatened by the Endangered Species Act. Overlooked for decades, these small stream mouths weren’t seen as important for Chinook salmon, but scientific research has revealed that these habitats are used by a portion of Chinook salmon populations.

“New science says these small fish use these stream mouths, so this is really a new type of recovery strategy.”

Susan O’Neil, ESA senior conservation planner.

Coast Salish Tribes, though, have been sounding the alarm. For millennia they’ve relied on these vibrant coastal habitats for livelihood and cultural traditions, and they saw a real-time decline in species. Acting upon new science they collected, the Tulalip Tribes have been instrumental in working with the company that owns the railroad, BNSF Railway, and other restoration partners on a collaborative solution to replace undersized culverts along the shoreline railroad to restore fish passage and the natural stream and estuary processes and habitats.

A Collaborative Approach to Habitat Restoration

The Tulalip Tribes partnered with ESA to help bring together a coalition of stakeholder partners including BNSF, the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife (WDFW), Puget Sound Partnership, and local project sponsors like Snohomish County. Each partner represented distinct interests around the common goal to take a regional approach to restore these important regional resources.

Phase 1: Regional Evaluation

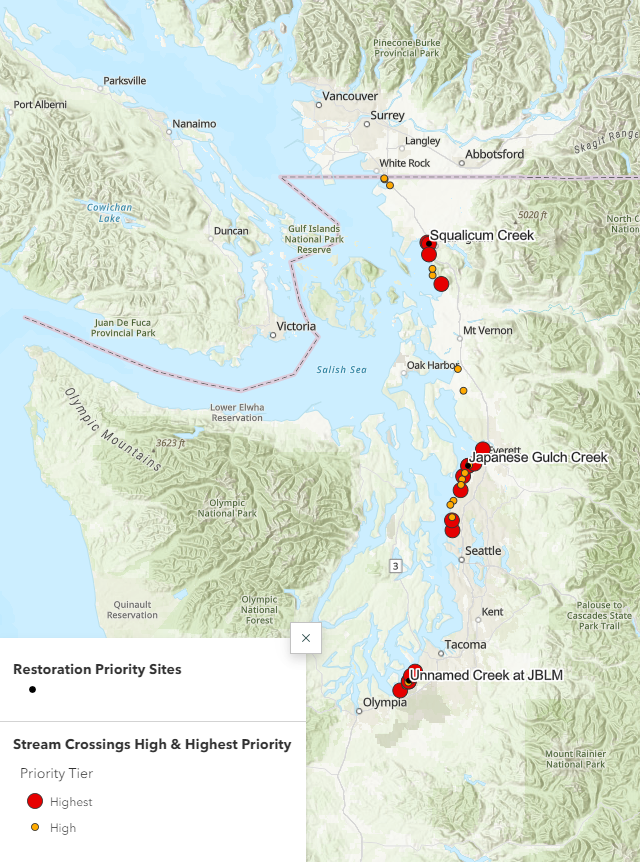

The project team evaluated 196 stream crossings and 13 embayments along the shoreline railroad between Olympia, Washington, and the U.S.–Canada border. Applying a prioritization framework to characterize the potential use of each stream or embayment by juvenile Chinook salmon, 45 priority streams and seven priority embayments were identified.

“We developed the evaluation framework to apply the state of the science to identify stream mouths and embayments where restoration would most benefit the recovery of Chinook salmon.”

Paul Schlenger, Principal Fisheries Biologist

Phase 2: Implementation at High-Priority Areas

Phase 2 of the project wrapped up in late 2022 with programmatic recommendations for implementing regional restoration along the railroad and designs for three high-priority areas: Squalicum Creek near Bellingham, Japanese Gulch Creek near Mukilteo, and a creek at Joint Base Lewis–McChord near Steilacoom. The programmatic recommendations include a set of site characteristics that need to be factored into restoration planning from the outset at any stream or embayment crossing along the railroad. This includes characteristics affecting the design and constructability of a replacement crossing.

Highlighting one of the three priority sites, the Squalicum Creek estuary project will replace three existing stream crossings with fish-passable bridge spans that use minimal in-stream supports and improve access for salmon to more than 35 miles of stream habitat. The restoration concept also includes removing fill material from the mouth of the creek to more than double the size of the estuary. Such restoration will also leverage the hard work being done by other local projects in the creek system that are conducting restoration and conservation efforts and are removing other passage barriers upstream.

The progress made in Phase 2 resulted from a highly productive dialogue with BNSF and restoration partners to begin planning for regional implementation to restore the priority sites.

Next Steps

The successful implementation of Phases 1 and 2 shows the potential to apply the science and advance work at all the high-priority areas as Phase 3. This may look different at each site, but ideally, all sites will have conceptual designs in the next year so that ESA, BNSF and partners can identify project bundles for implementation, apply guidance from WDFW on fish passage in tidal systems, and leverage the once-in-a-generation funding available to multi-benefit projects focused on infrastructure, natural solutions to climate impacts, and community improvements like public safety and beach access.

There is considerable energy across the U.S. to find collaborative solutions for habitat restoration while also maintaining important freight corridors. ESA is here to seek collaborative solutions based on science to find efficient, economical, and environmentally sound solutions. For more information about our work on habitat restoration and fish passage projects, please reach out to Paul Schlenger and Susan O’Neil from our northwest restoration team for more information.