Water-related climate change concerns often fall under two categories: not enough water (e.g., persistent droughts) or way too much water (e.g., disastrous flooding, intense hurricanes). Sea-level rise falls under the “too much water” category, which is causing an issue unique to coastal communities: increased flooding and the infiltration of seawater into crops relying on fresh water. There are many consequences to this, and one that ESA is working with farmers and landowners on is the effect of salinization on coastal farmland. Saltwater reduces yield for vulnerable crops, threatening viable farmland as sea levels rise. There is a solution, though, in the form of returning some of this land to its natural wetland state.

But first, let’s start with the problem at hand.

What Salinization of the Water Table Means

Before joining ESA, Sky Miller and Dan Elefant partnered with the Snohomish Conservation District and conducted an impact assessment for the Snohomish and Stillaguamish floodplains. The major takeaways are a trifecta of water-related impacts on coastal farmland: flooding, groundwater levels, and saltwater intrusion. Sea-level rise and groundwater levels are particularly interconnected: with sea-level rise, the groundwater table rises and saltwater intrusion increases, putting many crops at risk for both flooding and salination.

Sea-level rise and groundwater levels are particularly interconnected: with sea-level rise, the groundwater table rises and saltwater intrusion increases, putting many crops at risk for both flooding and salination.

As noted in the assessment: “Though salts are crucial plant nutrients, high concentrations of any one salt or many different salts can be toxic to plants.”

The assessment further determined the increased risk to crops planted closer to the shoreline. While many of the crops might not be particularly vulnerable at this moment, they could become increasingly at risk as the sea level rises, bringing more and more salinity into the groundwater source each year.

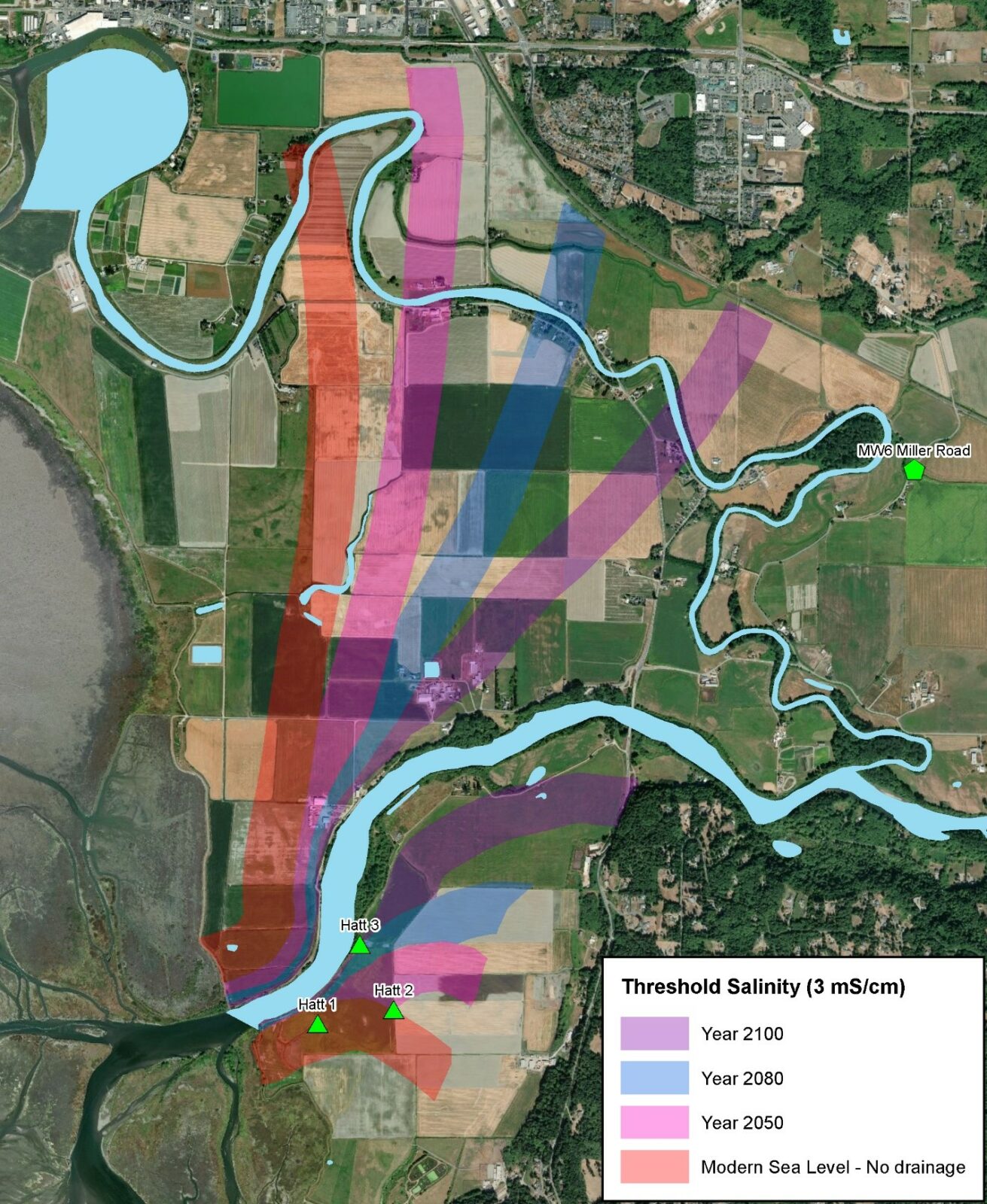

This salinity intrusion map developed by Dan Elefant for the Snohomish Conservation District, shows landward migration of salinity intrusion to groundwater without levee setback and drainage changes.

The Solution in the Form of Wetland Restoration

The solution that ESA and our partners are turning to is restoring farmland to its original state as an estuary. What early European settlers saw as fertile lands ripe for farming, were also vibrant ecosystems that tied the ocean to the inland through wetland estuaries teeming with wildlife. Many of these early farmers created dikes in these deltas, which consequently impacted the salmon and steelhead habitat.

Agricultural land in Bellingham, Washington.

“Now that climate change is of concern for agricultural resilience, many farmers are realizing that the proximity to the ocean is now a central problem,” says Sky Miller, ESA engineer. For instance, Washington’s Puget Sound is already eight inches higher than when the diking and drainage systems were constructed for agriculture, and we’re seeing the impact of that. In January 2022, a very intense low-pressure system created a record-high tide that raised Puget Sound two feet higher than would have occurred without the storm. This caused water to pour over the dikes at the Blue Heron Slough site. Merely raising the dikes to protect from these higher water levels would cost millions of dollars and would only be a temporary fix.

“Now that climate change is of concern for agricultural resilience, many farmers are realizing that the proximity to the ocean is now a central problem.”

Sky Miller, P.E., ESA Senior Principal Engineer

The Blue Heron Slough Project is a public-private partnership between the Port of Everett and Snohomish County, for which ESA’s Sky Miller, Dan Elefant, Hannah Snow, and Miranda Nelson provided construction management and engineering services. On nearly 350 acres between Everett and Marysville in Northwest Washington State, this project actually had its origins for Miller over three decades ago while surveying what was then Biringer Farms. He casually proposed to the landowners to restore the land to the original wetlands, but the idea took some time to take hold. Then, in 1993, the Port of Everett bought the property for the purpose of restoration and the project became the largest restoration undertaking in the history of the Port.

Fast forward to 2022, the project has reached fruition; the dikes are in the controlled breach stage and water has begun to flow back into the reclaimed wetland area from four breaches in the dike. The project also constructed 4,000 linear feet of protected dikes next to Interstate 5 and nine miles of channels to protect juvenile salmon and trout as well as other species central to the wetland ecosystem. As the controlled breach is happening, biologists have already seen juvenile Chinook salmon returning to the area.

Construction is underway to restore Blue Heron Slough following the first levee breach in September 2022.

“This is the first time in more than a century that this area has been reconnected with the river,” said Lisa Lefeber, CEO of the Port of Everett, during the September dedication ceremony. While this project began before much was known about the salinization of groundwater, this initial restoration is proving to be rather prescient to landowners as it shows the potential of their land beyond farming.

Many coastal tribes have also been active in restoring these wetlands. These original estuaries remain vital to the culture and resiliency of coastal tribes, who have a stake in restoring them by bringing back important species such as salmon and steelhead trout. “Habitats like this throughout the Northwest are threatened and tribes are doing a lot to make sure that when the opportunity comes to invest in restoration and protections of ones that still exist,” said Leonard Forsman, Suquamish Tribe chairman at the September dedication. Tulalip Tribal historian Tony Hatch also lauded the Port for also seeing the Tribes’ work as part of their work too: “We’ve been vanguards of our natural resources from time immemorial. We do everything we can to protect it and it’s nice to have others come in and help with that protection.”

“Habitats like this throughout the Northwest are threatened

and tribes are doing a lot to make sure that when

the opportunity comes, to invest in restoration and protections

of ones that still exist.”

Leonard Forsman, Suquamish Tribe Chairman

And we at ESA see the potential of these wetland estuary projects to encourage farmers to invest in places with more certain agricultural resiliency while allowing the coastal tribes to continue to protect the regions’ natural resources and wetland ecosystems.

“At ESA, we now have ten more estuary projects under various stages of design and construction,” says Sky Miller. “We’re doing a lot of this work because of organized retreat.” This means landowners are seeing the potential threat to their land and opting to move inland or try to sell off their land before it becomes unfarmable.

“While climate change most definitely poses concerns for landowners, farmers, and tribes, alike, these restoration efforts can make use of lands that may no longer be viable for agriculture in the long term, and help rebuild healthy salmon runs and Southern Resident Orcas.”